Letters to Memory

فرمت کتاب

ebook

تاریخ انتشار

2017

نویسنده

Karen Tei Yamashitaناشر

Coffee House Pressشابک

9781566894982

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from July 1, 2017

When the United States imprisoned Japanese Americans in internment camps during World War II, the circumstances changed the lives of more than 100,000 U.S. citizens, profoundly impacting future generations. In her first work of nonfiction, novelist Yamashita (literature, Univ. of California, Santa Cruz; I Hotel) uses her family's letters, sermons, and photographs to come to terms with this period's impact on both her family and American society as a whole. Told in a series of letters from Yamashita to fictionalized academics, the book muses on the value of debt, forgiveness, civil rights, and love to a family after the trust between country and citizen has been broken. Instead of dwelling on the injustice that befell her parents' community, Yamashita focuses on her father's rebuilding of his parish and her community finding a way forward through tragedy. VERDICT While this account may provide context for some of the themes found in Yamashita's fiction, the author's personal reflections on a dark period of American history will resonate with a larger audience concerned with how some U.S. organizations have targeted specific communities.--John Rodzvilla, Emerson Coll., Boston

Copyright 2017 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

July 15, 2017

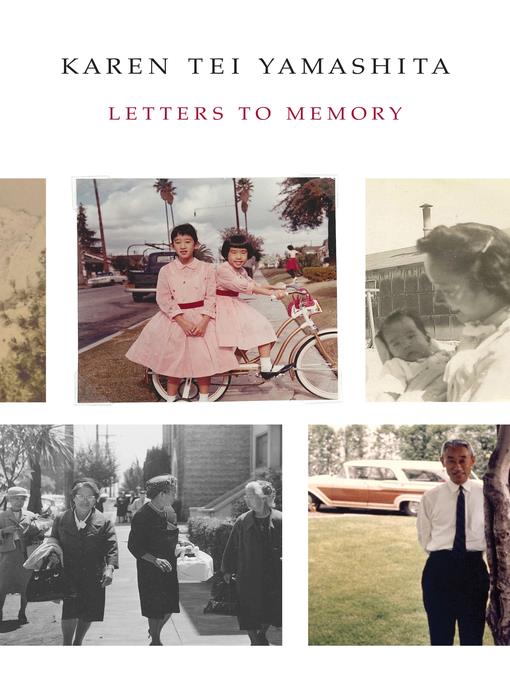

A multilayered evocation of Japanese internment camps as experienced by the author's extended family.The thematic ambition of this project transcends category. It isn't quite memoir or even the memory of stories told by earlier generations. Title aside, it isn't a collection of letters, though such an archive spurred Yamashita (I Hotel, 2010, etc.) to feel she could become "a useful repository of the past." She quotes the letters sparingly, and most of the longer letters are hers to readers or her editor. It isn't quite a scrapbook, though there are plenty of family photos, renditions of artwork, and shards of manuscripts. The narrative is part research, part history, part literary criticism, part spiritual meditation, and part open wound. "Stories blossom, as a kaleidoscope, a space where events aggregate in infinite designs," writes Yamashita, who has toyed with form in her much-lauded fiction. Most of these stories are ones she has read in the letters or maybe heard from her parents (her father was a pastor), but they become very much her stories in the telling. "For you, the problem is to separate the fiction from the fact of living," she writes, addressing "Homer," though perhaps writing to the reader or herself, "to excavate the origins of our attachments to meaning, the material forensics of human systems, the fork in the road where we could have taken another path. This is the work of history." This is certainly interpretive history that illuminates the tensions within the Japanese community in America over the war with Japan and the ironies of a country outraged by German concentration camps subjecting the Japanese in America to similar treatment. Shaped and voiced with literary flair, this is clearly a book Yamashita felt compelled to write, and her sense of purpose makes this historical excavation feel deeply personal.

COPYRIGHT(2017) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

July 24, 2017

Novelist Yamashita (I Hotel) explores her family’s experience in a Japanese-American internment camp during WWII using stories, letters, photos, artwork, and other records from her family archive. In five thematically linked sections on poverty, modernity, love, death, and laughter, Yamashita sketches the humiliation, absurdity, and cruelty collectively suffered by her extended family, with special focus on her grandmother Tomi; mother, Asako; and father, John. In one particularly haunting scene she imagines what it was like for her family to frantically pack their house in one day before leaving for the relocation camp. Yamashita positions these stories within larger questions—what is the meaning of evil, justice, war, and forgiveness?—and considers the answers suggested in classics including the Iliad, the Mahabharata, the jataka tales, and King Lear. The immediacy and poignancy of the struggles of Yamashita’s family members are deflated by interposed epistolary conversations with five mythic authors and pseudonymous scholars, who never take shape with the richness, complexity, urgency, or character of Yamashita’s family and friends. Yamashita’s hopscotch approach makes the deeper claim that there is no explanation and no possible reparation for events like slavery, internment, or the bombing of Hiroshima—only the disorienting reality they produce and the legacy of pain, distrust, and shame they leave behind.

دیدگاه کاربران