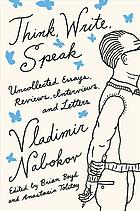

Think, Write, Speak

Uncollected Essays, Reviews, Interviews, and Letters to the Editor

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

September 2, 2019

The more than 150 essays, interviews, and letters collected in this volume, some translated from the Russian for the first time, serve as an illuminating complement to Nabokov’s 1973 nonfiction roundup, Strong Opinions. Spanning the years 1921 to 1977 and drawn from sources as diverse as the New Republic, Sports Illustrated, and journals for Europe’s Russian émigré community, they show the author to have been strongly opinionated on matters that run the gamut from literary style, to his discoveries as an amateur lepidopterist or the cultural impact of his controversial novel Lolita. Nabokov is passionate in his assessment of literary favorites such as Pushkin, whose work he praises for “its ample and powerful lyricism,” and bluntly critical of most Soviet literature, which he derides as propagandistic “village dreadful fantasies.” His incisive wit and intellectual honesty are also evident in his responses to interviewers’ repetitive questions about the scandal caused by Lolita. Nabokov observed, “I write what I like and some like what I write,” and his fans will find much to like here.

September 15, 2019

Scores of interviews reveal Nabokov's sly wit and powerful opinions. Award-winning biographer, editor, and literary critic Boyd (English/Univ. of Auckland; Why Lyrics Last: Evolution, Cognition and Shakespeare's Sonnets, 2012, etc.) and scholar and translator Tolstoy (Junior Research Fellow/University of Oxford; co-translator: Nabokov's The Tragedy of Mister Morn, 2013) have gathered more than 150 uncollected writings by the prolific Nabokov (Letters to Véra, 2014, etc.): essays, reviews, questionnaire responses, letters to editors, and--accounting for the majority of the pieces--interviews, most dating from the "post-Lolita years of world fame." An informative introduction places the selections in the context of Nabokov's life and writing career. After Lolita appeared in 1958, interviewers pressed Nabokov about not only the book, but also opinions of other writers, his decision to live in America (the "country where I've breathed most deeply," he said), his interest in butterflies, and his assessment of his own work. Boyd has condensed some of the more repetitive interviews. Nabokov claimed that his favorite book was the just-published Lolita, "the story of a poor, charming girl" who was "caught up by a disgusting and cruel man." To the suggestion that any of his books could be elucidated by Freudian interpretation, he was indignant: Freud, he proclaimed, "has been one of the most pernicious influences on literature...a medieval mind dealing in medieval symbols." Psychoanalysis, he added, "has something Bolshevik: internal police." Nabokov had similarly vehement opinions about a host of writers: Dostoevsky was "a journalist, like Balzac," and "Camus is a third-rate novelist." He admired Hemingway's short stories, but he thought his novels were "abominable." Of Nobel Prize winner Boris Pasternak, Nabokov derided Dr. Zhivago as "a sorry thing, full of clichés, clumsy, trivial and melodramatic." J.D. Salinger, though, was "a great, wonderful writer--the best American novelist." When asked what other career he might have chosen "if the muse failed," Nabokov suggested a lepidopterist, chess grandmaster, or a "tennis ace with an unreturnable service." A rich treat for Nabokov's admirers.

COPYRIGHT(2019) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

دیدگاه کاربران