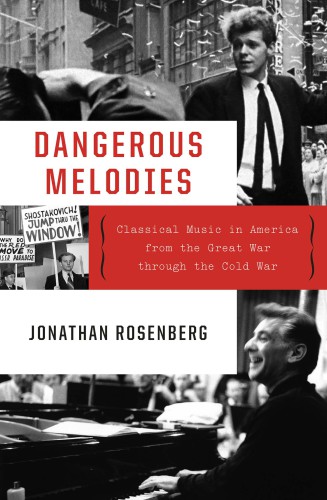

Dangerous Melodies

Classical Music in America from the Great War through the Cold War

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

September 23, 2019

Seemingly staid concert halls that were once roiled by ideological battles come into consideration in this probing study of the geopolitics of classical music. Hunter College history professor Rosenberg (How Far the Promised Land) starts with America’s musical hysteria during WWI, including riots against “German” music, purges of German (or German-American) musicians and conductors from orchestras, and bans on Wagner’s operas. The 1930s and ’40s, he notes, saw less jingoism but equally ferocious protests against musicians tied to Germany’s Nazi regime; meanwhile, Americans applauded Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich’s “Seventh Symphony” in 1942 to signal wartime solidarity with the Soviets. The Cold War saw America weaponize classical music against Soviet communism, in this telling, as orchestras and musicians went abroad to display American cultural achievements, climaxing in pianist Van Cliburn’s triumph at Moscow’s Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958, which won him a ticker tape parade back in New York. Rosenberg smartly frames this history as a battle between a “musical nationalism” that saw classical music as a projection of national diplomacy and influence, and a “musical universalism” that emphasized its power to unite humanity. Rosenberg’s prose can be dry, but classical music aficionados will find much enjoyable lore from a time when the music was at the center of international rivalries. Photos.

October 1, 2019

For half a century, classical music reflected America's identity on the world stage. In a thoroughly researched and engrossing history, Rosenberg (Twentieth Century U.S. History/Hunter Coll. and CUNY Graduate Center; How Far the Promised Land?: World Affairs and the Civil Rights Movement From the First World War to Vietnam, 2005, etc.) reveals the surprising connection between classical music and world politics from the early 1900s until the end of the Cold War. During these years, classical music became imbued "with political and ideological meaning" that helped Americans "decide what was worth fighting for and why. It helped to illuminate the meaning of democracy, freedom, and patriotism" as well as "tyranny and oppression." Because music seemed so potent a force, debate raged over which music and which performers should be heard in concert halls: Musical nationalists believed that certain composers, performers, or conductors could contaminate the nation and should be banned; musical universalists held that music transcended politics and "could speak to the hopes and dreams of all humanity." The two positions became violently opposed during World War I, when "uncontrolled xenophobia and hypernationalism" focused on Germans. Concerts and contracts were canceled, two acclaimed maestros were imprisoned, and "The Star-Spangled Banner" became a requisite part of an orchestra's repertoire. Americans, Rosenberg writes, "came to see Germans as demonic, whether they were fighting on a European battlefield or directing symphony orchestras." By the next war, however, universalists prevailed, and the idea of "enemy music" disappeared, replaced by "the notion that classical music, German compositions included, could help vanquish malevolent regimes." As Boston Symphony conductor Serge Koussevitsky put it, "of all the arts, music is the most powerful medium against evil." That sentiment continued during the Cold War, when the American government sent symphony orchestras and performers throughout the world "to display the fruits of liberal democracy to friend and foe." Among the stars of that effort was New York Philharmonic conductor Leonard Bernstein, who believed that classical music "might play a part in building a more compassionate and cooperative world." A richly detailed and freshly illuminating musical/political history.

COPYRIGHT(2019) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

November 1, 2019

The subject of this book might at first seem obscure, even acknowledging that classical music once played a far more prominent role in American cultural life than it does today. Imagine the selection of a conductor exciting nationwide comment, as it did in 1949 when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra offered a position to Wilhelm Furtwängler. Yet it's remarkable how much Rosenberg's (history, Hunter Coll.; How Far the Promised Land?) detailed study applies to current events and cultural discourse. His examination turns on the tension between nationalism and universalism, without ever declaring in favor of either. Instead, Rosenberg, a Juilliard-trained musician, highlights how global events and international politics impact aspects of cultural life that seem far removed from such concerns. The author convincingly argues that art, and discourse around art, does not take place in a vacuum--and that the tension he describes will never be truly settled. VERDICT A clear-eyed and perspicacious work for classical music scholars and fans and anyone interested in the intersection of politics and culture.--Genevieve Williams, Pacific Lutheran Univ. Lib., Tacoma

Copyright 2019 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

December 1, 2019

From the U.S. entering WWI to Nixon's trip to China in 1971, classical music was a cultural weapon for Americans. Behaving appropriately, they thought, as citizens of a combatant country, influential and ordinary Americans alike raged against German music during the First World War, leading to the internment of the principal conductors of two major U.S. orchestras and many musicians and the banishment of Wagner and Richard Strauss from concert programs. Before and during WWII, similar zealots didn't again decry German music and musicians, but afterwards, they attacked musicians (e.g., conductor Wilhelm Furtw�ngler and pianist Walter Gieseking) who hadn't left Germany for the duration. As the Cold War settled in and classical-music warriors set their sights on Russians (especially composer Dmitri Shostakovich, a WWII artistic hero), the U.S. government decided music was a good diplomatic weapon and, inspired by Van Cliburn's first-placement in the International Tchaikovsky Competition, dispatched American orchestras to the USSR. Drawing on primary sources near-exclusively, Rosenberg masterfully tells these stories straightforwardly, refreshingly leaving connections to other cultural currents for others to spin.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2019, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران