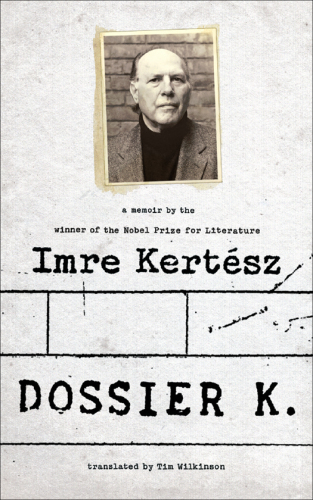

Dossier K

A Memoir

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from April 8, 2013

Hungarian author Kertész (Kaddish for an Unborn Child), winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize for Literature, pens an unflinching memoir in the form of a Socratic dialogue with himself about his extraordinary life. Noting that “a good autobiography is like a document: a mirror of the age on which people can ‘depend,’ ” Kertész unearths memories of his childhood in Budapest, his adolescent imprisonment in Nazi concentration camps, his pursuit of journalism in Communist-dominated Hungary, his two marriages, the eventual publication of his novels, and the relation between his life and literary career. The unsentimental and provocative author explores his views on religion: “I’m prone to mystic experiences, but dogmatic faith is totally alien to me.” He also discusses philosophy; Communism and his reasons for joining the Party; the legacy of the Holocaust; the influence of Thomas Mann, Albert Camus, and Franz Kafka on his work; and more. Kertész is meditative, insightful, profound, and unafraid to confront difficult questions and biases: “Anyone who is right generally proves not to be right. We need to have respect for man’s fallibility and ignorance....” He finds that writing gives him his greatest joy and believes it can only come from an “abundance of energies, from pleasure; writing... is heightened life”—and so is his memoir.

May 1, 2013

Kertesz, the first Hungarian writer to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, interrogates himself in a provocative memoir that will deepen the understanding of those already familiar with his novels. Published in 2006, this unusual transcript receives its first English translation and American publication, providing the author's perspective on novels that challenge the distinction between fiction and reality as well as conventional notions of the Holocaust and totalitarianism. His renown rests on a series of novels--Fatelessness (1975), Fiasco (1988) and Kaddish for an Unborn Child (1990)--that were little-known in the West until after the Nobel and which have frequently been described as unsentimental. After a childhood in a broken family in Budapest, Kertesz was imprisoned in Nazi death camps at the age of 14 and survived due in part to a forged record of his death. He subsequently became a journalist and a communist following the end of the war before turning to fiction. He rejects the very term "Holocaust" as "a euphemism, a cowardly and unimaginative glibness," while spurning the conventional categorization of his work: "I never called Fatelessness a Holocaust novel like others do, because what they call 'the Holocaust' cannot be put into a novel." Kertesz acknowledges the profound influence of and his deep affinity for Kafka, Mann and Camus, while maintaining, "I don't know what the truth is. I don't know whether it is my job to know what the truth is, in any case. Truth-telling artists generally prove to be bad artists. Anyone who is right generally proves not to be right." Such provocation fills practically every page of this memoir by an author who hasn't mellowed with age and who continues to believe that "everything is in flux, there is no foothold, and yet we still write as though there were." The author's novels may provide a better introduction to his work, but this memoir will help to further illuminate them.

COPYRIGHT(2013) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

May 1, 2013

Kert'sz received the Nobel Prize in 1992, and his first novel, Fatelessness (1975), ranks among the half-dozen most important and instructive works about the Holocaust. Dossier K. is further evidence, if needed, that Kert'sz's sensibility defies classification. To call him unique would be to miss the point; it would diminish his frankness, his modesty, his shocking honesty that, he would remind us, is not the same as telling the truth. Dossier K. appears to be an extended interview. Kert'sz as biographer questions Kert'sz the autobiographical novelist (he was deported to Auschwitz from Budapest as a teenager, and liberated from Buchenwald in 1945) about his life, trying and resolutely failing to create a narrative arc from that deeply unfashionable excess called existence: One is not born for anything in particular, but if one manages to stay alive long enough, then one cannot avoid eventually becoming something. There are myriad insights in this book, more than enough to occupy an open, inquisitive mind for years. A necessary work, beautifully translated.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2013, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران