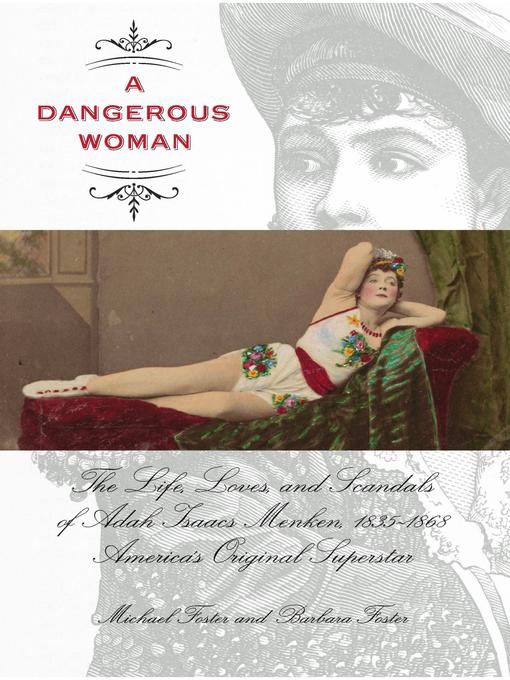

Dangerous Woman

The Life, Loves, and Scandals of Adah Isaacs Menken, 1835-1868, America's Original Superstar

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

November 29, 2010

The beautiful and charismatic actress and poet Menken deserves a better biography than the tedious narrative delivered by the Fosters (Forbidden Journey: The Life of Alexandra David-Neel). Menken became famous for wearing little while dashing up an artificial mountain strapped to the back of a horse in Mazeppa, a popular play of the 1860s. She frequently dressed as a man, smoked cheroots, married five times, was an ardent Zionist, had male and female lovers—all before dying at 33 of consumption. Describing her theatrical itineraries in detail and repeatedly reporting rave reviews while dismissing negative critiques as products of prudery, the Fosters speculate on Menken's psyche, claiming to lay bare her "orphaned inner child." Clichés abound (in 1861 the U.S. "hesitated on the brink of war"; Menken's second husband "ran fast as a deer" from an illegal boxing bout; and her career was "like a shooting star"). Readers interested in Menken will find the authors' Web site (www.TheGreatBare.com) better written and more engaging.

December 1, 2010

One of the first media superstars receives an uninspiring biography.

The Fosters (The Secret Lives of Alexandra David-Neel: A Biography of the Explorer of Tibet and Its Forbidden Practices, 1997, etc.) chart the life and career of Adah Isaacs Menken (1835–68), an actress and poet who briefly captivated the world in with her iconic turn in the play Mazeppa, in which she played a male Cossack and, in a sensational set piece, rode a horse up the side of a four-story artificial mountain, clad in not much more than a pair of pink tights. The danger and provocative sexuality attending this stunt cemented Menken's status as a "dangerous woman" and media superstar, but contemporary scholars are more interested in pinning down the actress's vague ethnicity and identity politics—she has been variously identified as a woman of color, a Jew and a lesbian (or at the very least bisexual). The authors enthusiastically explore these possibilities, but a crippling dearth of verifiable evidence reduces their sleuthing to a convoluted series of educated guesses. What is certain is Menken's status as a proto–sex symbol and feminist touchpoint. Her multiple husbands included famous boxer John Heenan and Alexander Menken, a Jewish musician—this union would lead to Menken's conversion to Judaism and her stridently pro-Jewish poetry. The Fosters praise Menken's writing profusely, but the work excerpted here is didactic and shrill. She did enjoy many high-profile literary friendships, including relationships with Mark Twain, Charles Dickens and Alexandre Dumas, but the Fosters fail to establish their heroine as a significant artist in her own right. Her lasting contributions boil down to a series of slightly hysterical poems, a starring role in a crowd-pleasing spectacle and some racy photographs. More troubling, Menken, who must have cut a charismatic figure, fails to come to life in the Foster's pedestrian prose. The authors exhort the reader to appreciate Menken's singular nature, but she remains an enigma, and the catalog of her lovers, confidants, enemies, professional reversals and emotional crises becomes a tedious litany of woe.

A dull account of a largely forgotten American icon.

(COPYRIGHT (2010) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

دیدگاه کاربران