Elizabeth and Hazel

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

July 4, 2011

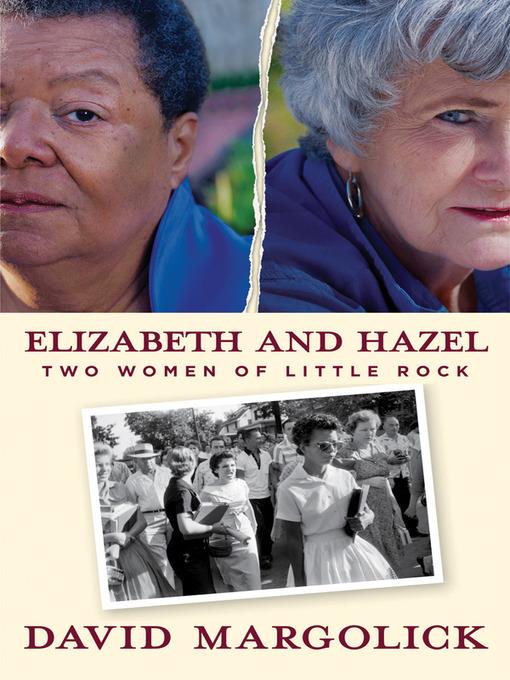

Vanity Fair contributing editor Margolick (Beyond Glory) brings his considerable skill to telling a tale many may, mistakenly, think they already know. Bound together in the iconic photograph of the integration of Little Rock's Central High School in which the white Hazel Bryan is caught screaming epithets at the stoic black student, Elizabeth Eckford, the two women went on different paths charted by this sympathetic and readable dual biography. Elizabeth survived the horrendous harassment of her high school years, and the lavish attention upon the Little Rock Nine, followed by a difficult early adulthood. While Hazel's high school years, spent in anonymity at another school, are more halcyon, her early adult years are difficult as well. For both young women, the experience and the photograph that was to follow them were transformative. Margolick pays particularly insightful attention to the photographs and media coverage stimulated not only by the event but all the ensuing anniversaries. As Margolick moves through Elizabeth's days at Central High with new and meticulous detail, he gives Hazel a young life as well before turning to the separate years before they actually meet. Here Margolick's book becomes utterly engrossing, for it touches on a variety of thorny, provocative themes: the power of race, the nature of friendship, the role of personality, the capacity for brutality and for forgiveness.

July 15, 2011

An event of racially charged intimidation, captured on film, has lasting repercussions for two women.

Margolick spent 12 years researching the interlocking histories of Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan Massery, two students—black and white, respectively—who simultaneously attended Arkansas' Little Rock Central High School in the 1950s. Eckford, a smart student with lawyerly aspirations, was strictly raised in a squat, crowded house. Massery, the daughter of a wounded World War II veteran, was brought up poor but hopeful and easygoing, and she frequently played with black children as a girl. Though "Little Rock in the Eisenhower era was a racial checkerboard," writes the author, its looming high school still became the first Southern institution to become desegregated, which sent Eckford, along with eight other school board–selected black student "trailblazers" (the "Little Rock Nine"), into predominantly white classrooms. This fact incensed the 15-year-old Massery, who, backed by 250 angry, prejudiced white citizens, severely bullied Eckford, an action that was captured and immortalized on film by newspaper photojournalist Will Counts. Massery remained remorseless as the fallout from her actions included denouncement from both segregationists and the general public. Eckford, together with her integrated classmates, would go on to endure years of abuse in school. Margolick's impressively thorough examination is unique among other Central High exposés in that it incorporates updated material culled from media sources including interviews with eight of the school's nine black students and statements in Eckford and Massery's own words. Both of these women, he writes, were unenthusiastic about revisiting their ordeal, even to simply set the record straight—which the author accomplishes with graceful tact. Decades later, Massery's atonement and redemption manifested in an amicable but disappointingly short-lived friendship, joining Eckford as she accepted presidential accolades and while antagonistically interviewed on Oprah. The narrative concludes with the pair's discordant severance. "At this point," he writes, "only Photoshop could bring them together."

Riveting reportage of an injustice that still resonates with sociological significance.

(COPYRIGHT (2011) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

Starred review from August 1, 2011

In September 1957, Elizabeth Eckford attempted to enter Little Rock Central High School. One of what became known as the Little Rock Nine, she was prevented from entering the building and headed to a nearby bus stop instead, followed by an angry mob that included Hazel Bryan. Just as Bryan was screaming at Eckford, a journalist snapped a photo that came to define not only integration in Arkansas but, as Margolick (Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song) shows, the lives of Eckford and Bryan. There are volumes of scholarly works on the Civil Rights Movement, but this book is different. By tracing the two women's journeys from that moment until today, often in their own words, Margolick artfully lays bare the emotional and mental wounds and struggles of the participants. Both are presented as human, complete with flaws and weaknesses. Margolick also places the women in the context of the wider civil rights era and beyond. The ending is not what you would expect or even hope for but instead demonstrates how much pain is still felt by all involved and how far we all have still to travel. VERDICT Very thoughtfully and sincerely written, this work is simply a must-read. [Previewed in "Booked Solid," LJ 7/11.--Ed.]--Lisa A. Ennis, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham Lib.

Copyright 2011 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

Starred review from September 15, 2011

When Elizabeth Eckford braved the gauntlet of white hecklers leading to the newly desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957, photographers captured her image and that of the angry young white woman behind her. Elizabeth, the stoic, and Hazel Bryan, the tormentor, were frozen as icons. Elizabeth was part of the Little Rock Nine, the black teens who became the targets of race hatred as well as national and international inspirations. Despite public-relations efforts to depict the success of the Nine and the overall move to desegregation, the truth was far more complicated, particularly for Elizabeth. Margolick draws on interviews and press reports of the time to present a very nuanced analysis of how Elizabeth and Hazel were affected by the scene that made them famous. Elizabeth spent the remainder of her life a near recluse, scarred by the memory of that day, adrift emotionally, dodging the commemorations. In contrast, Hazel opened up, evolving into a free-spirited progressive. Hazel, who didn't even finish her year at Central High, later reentered Elizabeth's life with a heartfelt apology that went unreported until the two women reunited for a symbolic reconciliation and photo op back at Central. A complex look at two women at the center of a historic moment.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2011, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران