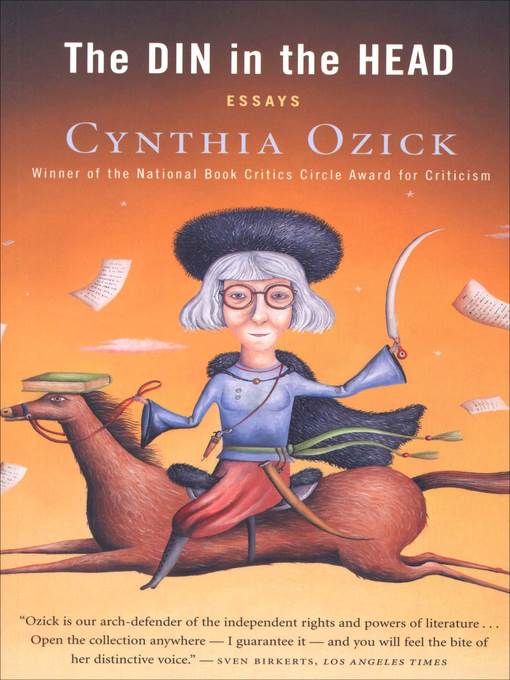

The Din in the Head

Essays

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

April 24, 2006

Reviewed by Daphne Merkin

Ever since she first started offering up her fiercely (and often unfashionably) judgmental opinions over three decades ago, the din in Cynthia Ozick's head has been worth listening to—even if you don't agree with her conclusions. "This persistent internal hum," as she characterizes it in her latest essay collection, is set off most memorably by "the individual's solitary engagement with an intimate text," be it John Updike's early stories, Sylvia Plath's journals, or Robert Alter's new translation of the Pentateuch. In our cacophonous Age of Buzz, where eloquent literary reflection has gone the way of Wite-Out, Ozick prides herself on resisting the blandishments of popularity for the highbrow's more discriminating vantage point. "Readers are not the same as audiences," she reminds us sternly in "Highbrow Blues," "and the structure of a novel is not the same as the structure of a lingerie advertisement."

Although Ozick is equipped with the kind of intellectual muscle that marked Susan Sontag's strongest writing—the opening essay, "On Discord and Desire," pays qualified homage to Sontag—she also has a rigorous (some might say self-righteous) moral sense and a distrust of radical chic that draws her to burnishing eclipsed reputations, which she does in moving appreciations of Lionel Trilling and Delmore Schwartz, and to upholding classical values, as espoused by Saul Bellow or the Bible. Ozick is most effective when she has more rather than less room to expatiate; the best pieces here are capaciously rendered, like an inspired reconsideration of Gershom Scholem.

To be sure, at however exalted an altitude she pitches her criticism, Ozick is not above fretting about the vagaries of celebrity and, indeed, seems never to have accommodated herself to the relative obscurity that attends upon a more elitist calling. I assume it is to this end that we are treated once again to an account of her youthful obsession with writing a Jamesian novel ("James, Tolstoy, and My First Novel")—a miscalculation that clearly preys on her. Perhaps it is her wish to make up for her late start that has led her to include every piece of occasional writing she has done (including a review of Joseph Lelyveld's memoir, Omaha Blues

, that I remember reading the first time around). If this collection is not the strongest of the four she has published, Ozick's is a strikingly independent and articulate voice, one that rises above the noise of the madding crowd with rare clarity and force.

Daphne Merkin is the author of

Enchantment, a novel, and

Dreaming of Hitler, a collection of essays. She is a contributing writer for the

New York Times Magazine and writes a bimonthly book column, Provocateur, for

Elle.

May 29, 2006

Ever since she first started offering up her fiercely (and often unfashionably) judgmental opinions over three decades ago, the din in Cynthia Ozick's head has been worth listening to\x97even if you don't agree with her conclusions. "This persistent internal hum," as she characterizes it in her latest essay collection, is set off most memorably by "the individual's solitary engagement with an intimate text," be it John Updike's early stories, Sylvia Plath's journals, or Robert Alter's new translation of the Pentateuch. In our cacophonous Age of Buzz, where eloquent literary reflection has gone the way of Wite-Out, Ozick prides herself on resisting the blandishments of popularity for the highbrow's more discriminating vantage point. "Readers are not the same as audiences," she reminds us sternly in "Highbrow Blues," "and the structure of a novel is not the same as the structure of a lingerie advertisement." Although Ozick is equipped with the kind of intellectual muscle that marked Susan Sontag's strongest writing\x97the opening essay, "On Discord and Desire," pays qualified homage to Sontag\x97she also has a rigorous (some might say self-righteous) moral sense and a distrust of radical chic that draws her to burnishing eclipsed reputations, which she does in moving appreciations of Lionel Trilling and Delmore Schwartz, and to upholding classical values, as espoused by Saul Bellow or the Bible. Ozick is most effective when she has more rather than less room to expatiate; the best pieces here are capaciously rendered, like an inspired reconsideration of Gershom Scholem.To be sure, at however exalted an altitude she pitches her criticism, Ozick is not above fretting about the vagaries of celebrity and, indeed, seems never to have accommodated herself to the relative obscurity that attends upon a more elitist calling. I assume it is to this end that we are treated once again to an account of her youthful obsession with writing a Jamesian novel ("James, Tolstoy, and My First Novel")\x97a miscalculation that clearly preys on her. Perhaps it is her wish to make up for her late start that has led her to include every piece of occasional writing she has done (including a review of Joseph Lelyveld's memoir,Omaha Blues , that I remember reading the first time around). If this collection is not the strongest of the four she has published, Ozick's is a strikingly independent and articulate voice, one that rises above the noise of the madding crowd with rare clarity and force. - Reviewed by Daphne Merkin, author of Enchantment, a novel, and Dreaming of Hitler, a collection of essays. She is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and writes a bimonthly book column, Provocateur, for Elle.

دیدگاه کاربران