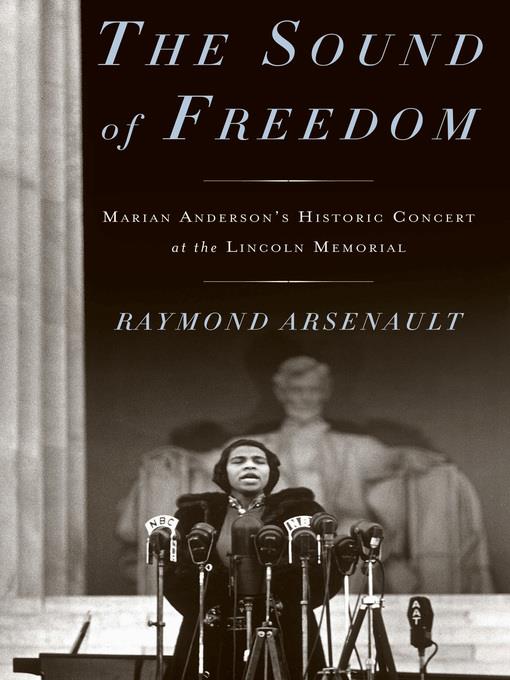

The Sound of Freedom

Marian Anderson, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Concert That Awakened America

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from March 30, 2009

Commemorating the 70th anniversary of African-American contralto Marian Anderson's culture-shifting 1939 Easter Sunday performance at the Lincoln Memorial, the story of this underappreciated Civil Rights milestone resonates even louder in the wake of President Obama's election. Civil rights historian Arsenault (Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice) paints a detailed portrait of America's struggle for racial equality through one of the 20th century's most celebrated singers (of any color). Despite a 40-year career as a world-class entertainer, performing around the globe, Arsenault suffered innumerable racist indignities in her homeland, culminating in the controversial declaration by the Daughters of the American Revolution that barred her from performing in Washington, D.C.'s Constitution Hall. In defiance, Anderson and her entourage arranged for the free, open-air Easter concert, which drew an estimated crowd of 75,000. The peaceful demonstration struck a vital blow for civil rights, and in particular for integration at Constitution Hall, nearly 25 years before Martin Luther King's march on Washington. Arsenault relies heavily on historical manuscripts and newspaper articles, but his vivid understanding of the players keeps the narrative fresh and insightful. Anderson died in 1993, at age 96, but this vivid tribute to her work and times does her memory a great service.

March 15, 2009

Arsenault (History/Univ. of South Florida, St. Petersburg; Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, 2006, etc.) examines the life of singer Marian Anderson (1897–1993), focusing on her landmark 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial.

A prodigiously talented vocalist, Anderson embarked on a career in music at a time when prevailing racial prejudices hindered African-American performers from attaining national prominence. Though she gained limited notoriety in the United States during the 1920s, it was her exhaustive tours of Europe during the following decade that established her as one of the world's most renowned vocalists. Her critical and popular success abroad enabled her to reach a wider audience in America, even though she continued to face discrimination. Notably, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to allow Anderson to perform at Constitution Hall, which maintained a strict"white artists only" policy. The DAR's decision sparked a nationwide controversy. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR in protest, while several newspaper editorials drew parallels between racial discrimination in America and the rising fascist movements in Europe. With the DAR standing its ground, Anderson and her supporters staged an outdoor concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. In front of 75,000 people on Easter Sunday in 1939, Anderson gave a concert that, writes Arsenault, provided a"starting point" for the civil-rights movement. The author excels at contextualizing the concert, probing the ways in which Jim Crow laws and racial prejudices permeated all aspects of African-American life. He is less adept at humanizing Anderson's struggle. The author's dry prose fails to capture the emotions surrounding the historic concert, or to convey the full impact of Anderson's performance. Looking back on the event, Anderson recognized that she had been turned into"a symbol, representing my people." Arsenault is unable to draw out the individual behind that powerful symbol.

A concise but flat-footed chronicle of a seminal event in civil-rights history.

(COPYRIGHT (2009) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

April 1, 2009

Marian Anderson rose from humble beginnings in Philadelphia to become a world-renowned contralto and one of the most prominent African American women of her time. Arsenault (John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History, Univ. of South Florida; "Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice") adds to the large body of literature on Anderson with a book focusing on her iconic 1939 Easter concert. Having been denied the right to perform in Constitution Hall because of its white-performers-only policy, Anderson sang for 75,000 people on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Arsenault writes that this was the "first time anyone in the modern civil rights struggle had invoked the symbol of the Great Emancipator in a direct and compelling way," with Anderson striking a historic blow for civil rights. While readers should be aware of Allan Keiler's more general "Marian Anderson" or Anderson's own autobiography, "My Lord, What a Morning", Arsenault's book is a good one for serious students of the civil rights movement.Jason Martin, Univ. of Central Florida Libs., Orlando

Copyright 2009 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

July 1, 2009

Adult/High School-This account of a historic 1939 event begins with a description of Anderson's early nurturing by family and church. Arsenault also details her encouragement by the black community, mentoring by Roland Hayes, and instruction by voice coach Giuseppi Boghetti. Performances in the 1920s subjected Anderson to a spectrum of racism shaded by the mores of particular American communities. In Europe, however, her great voice was enthusiastically welcomed. In the Soviet Union, her rendition of Negro spirituals moved a secular audience to near pandemonium. Race, however, remained an issue at home. As plans were made for Anderson's Howard University Lyceum concert, it became clear that the usual Washington venue would not hold the expected attendees. The Daughters of the American Revolution Constitution Hall was requested, but the strategies of impresario Sol Hurok, the efforts of the NAACP, censure by the press, and Eleanor Roosevelt's resignation from the DAR could not convince that organization to allow a Negro to perform in its hall. The result was the thrilling concert before a wholly integrated audience of 75,000 at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial. Although this account focuses on the events leading to that performance, the author insightfully describes the people orchestrating Anderson's career and the political and social realities of the times. News reports and quotes are seamlessly incorporated, and quality black-and-white photos enhance the text."Jackie Gropman, formerly at Fairfax County Public Library System, Fairfax, VA"

Copyright 2009 School Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران