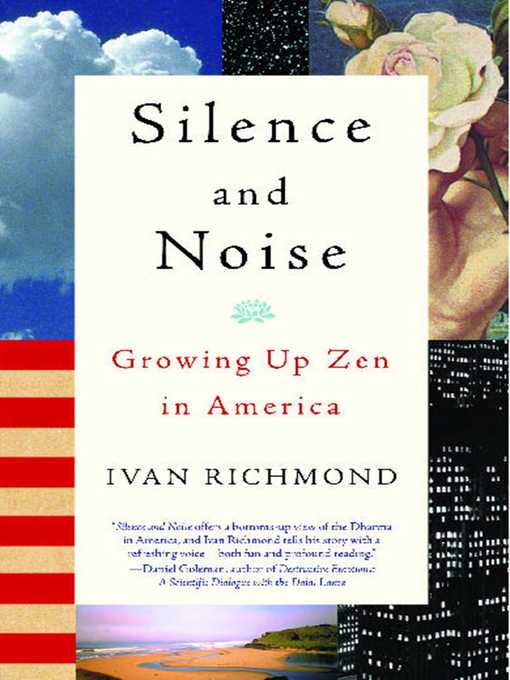

Silence and Noise

Growing Up Zen in America

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

May 26, 2003

The "convert Buddhism" of the 1960s has been around long enough to produce a second generation of practitioners. Son of businessman and author Lewis Richmond, Ivan (now 28) spent his childhood years at Green Gulch, the rural San Francisco Bay area Zen monastery. Those silence-drenched early years were spiritually formative, making the younger Richmond a native Buddhist who found, and continues to find, himself out of place in the larger American culture—materialistic, trend-conscious, noisy, Judeo-Christian—to which his parents returned when he was only 10. Richmond writes as a "rank and file Buddhist" rather than a master or teacher, distinguishing his perspective from most authors in the body of American Buddhist practitioner writings. He manages nonetheless to teach about Buddhism by laying out apparent contradictions in his experience and then explaining a Buddhist "middle way" in which he lives with the tensions of being a silence-loving non-materialist in a noisy consumer culture. His unadorned expository style nicely embodies the plain-experience quality of Zen; the lack of unfolding dramatic narrative that conventionally ought to characterize a life story is also distinctively Zen-like. This quiet tale is a good social study of being young, Zen and American.

July 1, 2003

Common wisdom says that the young should not write autobiography: they have no long view, no developed judgment, and no deepened grace of character, and they cannot as yet see much of life's direction. These two memoirs validate the rule. Levine, 32, is the son of well-known Buddhist author/teacher Stephen Levine and himself a teacher of meditation who works especially with adult and juvenile prisoners in the San Francisco Bay Area. Richmond, 28, is the son of Lewis Richmond, author and former tanto (head priest) at Green Gulch Farm, a branch of the San Francisco Zen Center. Both are thus second-generation, white, American-born Buddhists, and they both struggled (and continue to struggle) to reconcile their Buddhist upbringing with the pressures of hurly-burly, materialistic American society. In itself, this is not unusual-not only Buddhists but Christians, Jews, Hindus, Muslims, and others struggle in the same way. Levine, a rebel from childhood, fled into the punk rock scene, where he spent his youthful energy in promiscuity, drugs, and "rage against the machine." Richmond, a quieter and more docile youth, found himself stuck between the opposites of silence and noise, patience and impatience, letting go of and clinging to material goods. Interestingly, they both claim to have suffered from parental neglect, receiving no regular guidance or supervision from parents so deeply involved in religious practice that they had no time or energy for mundane family life. Their parents only sporadically seemed to recognize their negligence but were unable to change it. Levine and Richmond have not been able to overcome resentment for what they suffered as children, and it colors their outlook. Unfortunately, we've heard it all before and will again. Further, both books have problems of diction. Levine's is full of punk slang, contains some vulgarity, and is not always grammatical (though the review was done from uncorrected proof). Richmond's is grammatical but repetitive. Finally, no real insights are offered here; neither author convinces the reader that his childhood was unusual or exemplary. Not recommended.-James F. DeRoche, Alexandria, VA

Copyright 2003 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران