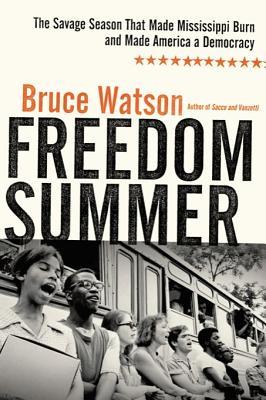

Freedom Summer

The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from May 3, 2010

In this mesmerizing history, Watson (Sacco and Vanzetti) revisits the blistering summer of 1964 when about 700 volunteers arrived in Mississippi to agitate for civil rights and endured horrific harassment, intimidation, and persecution from racist state and private forces. The largely white, college student volunteers and the largely black trainers and organizers, SNCC veterans of previous campaigns, were fed and sheltered by the impoverished black community members they had come to serve and secure suffrage for. Their path was two-pronged: the Freedom School’s challenge to a “power structure... that confined Negro education to ‘learning to stay in your place’ ” and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s challenge to Mississippi’s all-white delegation to the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Familiar figures (e.g., Lyndon B. Johnson, Stokely Carmichael, Fannie Lou Hamer) take the stage, but Watson’s dramatic center belongs to four “ordinary” volunteers, whose experiences he portrays with resonant detail. The murdered Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner cast shadows over all, haunting Watson’s account of how the volunteers, organizers, and the black Mississippians who dared seek political expression “lifted and revived the trampled dream of democracy.”

March 15, 2010

Blow-by-blow account of the ghastly reception given the Freedom Summer volunteers who attempted to register black voters in Mississippi in 1964.

Journalist Watson (Sacco and Vanzetti, 2007, etc.) creates a complete picture of this decisive summer, from the makeup of the young students who risked their lives to volunteer to a comprehensive portrait of a nation on the brink of wrenching change in race relations. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had recruited across college campuses legions of white and black students eager to break open the deeply segregated"closed society" of Mississippi, with its entrenched obstacles to black voting. Trained briefly in Ohio and bused down to Mississippi by late June, the young, idealistic volunteers were well-informed about the white hostility and customary savagery perpetrated against blacks that they would face. However, the largely middle-class, well-educated students were not prepared for the scenes of poverty and destitution they encountered in black communities throughout the South. The disappearance in late June of three SNCC volunteers haunted their work that summer, and the incident serves as the book's suspenseful propulsion. The discovery of their remains in early August—after an extended FBI hunt and national outcry—reinforced rather than deterred the volunteers' conviction. Watson does a fine job portraying key participants, such as SNCC leaders Bob Moses and Fannie Lou Hamer, as well as less-well-known events at the subsequent Atlantic City Democratic Convention in mid-August, where the 67 black Freedom Democrats of Mississippi insisted on being heard. Engaging but occasionally longwinded, Watson's work is competently researched and contextually rich.

A moving record of the power of idealism.

(COPYRIGHT (2010) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

May 1, 2010

Even those familiar with the history will want to read this gripping narrative, which combines a political overview of the Mississippi civil rights struggle in the summer of 1964 with more than 50 personal accounts from those who were there, both the famous (including Sidney Poitier, Pete Seeger, John Lewis, Stokely Carmichael) and the lesser known, including the more than 200 volunteer students from the North who lived and worked with local residents and taught in the Freedom Schools in converted shacks and church basements. The lengthy bibliography testifies as to how much has been written on the topic, but the personal interviews, some from people telling their stories for the first time, make gripping drama, as they recount the standoffs, the struggle for voter registration, the reign of terror that encompassed church burnings and murders. Ordinary people are the focus here, and the close-up details about the shocking violence and economic oppression show that even at the time of the famous I Have a Dream speech, sharecroppers earning $500 a year could not afford to eat at lunch counters.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2010, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران