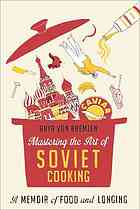

Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking

A Memoir of Food and Longing

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

August 26, 2013

Author of several international cookbooks, Moscow-born von Bremzen immigrated to U.S. shores with her mother in 1974. Here, she unlocks conflicted memories of her Soviet upbringing through reminiscences of certain dishes that became her very own “poisoned madeleines.” The period covered by the book begins with the fall of the czar in 1917 and ends with the triumphant return of the mother-and-daughter duo to “Putin’s mean petro-dollar capital” in 2011 in order to do their very own TV cooking show. Each decade is represented by foods that evoke emotional volumes: the fussy, decadent pre-Revolution aristocrat’s diet of burbot liver and viziga gave way to Lenin’s culinary austerity, exemplified by a spartan apple cake; the labor-intensive gefilte fish made by the author’s Jewish grandmother in Odessa was deemed unpatriotic and was replaced by utilitarian kotleti (Russian hamburgers); and food shortages and the rationing of the 1940s prompted “sham” foods for the starvation diet. The fluctuating political winds of the Soviet state were harnessed in successive editions of the totalitarian culinary bible, The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, where American and Jewish ingredients were unceremoniously deleted during the 1950s Cold War. Corn, caviar, mayonnaise, and vodka: for both von Bremzen and her mother, a teacher, these were the subjects of intense longing, as they endured living in a communal apartment with 18 other people and being abandoned by von Bremzen’s father, as well as regimented schooling and harassment as Jews. Recipes included. Agent: Andrew Wylie, Wylie Agency.

August 1, 2013

Travel + Leisure contributing editor and three-time James Beard Award-winning cookbook author von Bremzen's (The New Spanish Table, 2005, etc.) nostalgia for a prickly Soviet childhood brings memories of food both delectable and biting. Toska, "that peculiarly Russian ache of the soul," periodically stalks the author and her mother, Larisa Frumkin, who emigrated together from the Soviet Union to Philadelphia in 1974, when the author was 10. Although daily existence back in the Soviet Union had been harsh--anti-Semitic harassment, little support from a philandering father, and rough living conditions, including a lack of privacy, food shortages and lines for basic items--mother and daughter have found in food and cooking a way to capture their essential "Soviet homeland," even if it's more the idea of it than the way it ever really was. The author and her fervently dissident mother have re-created, in their tiny kitchen, certain foods that seem emblematic of each decade of the Soviet saga, from the pre-revolution time through the Stalinist era, World War II deprivations, Cold War classics and the "mature Socialist" period of the author's upbringing. For example, the impossibly decadent czarist fish pastry Kulebiaka delineated so seductively by Chekhov and Gogol marks the 1910s; Gefilte fish is the "poisoned Madeleine" of Larisa's childhood in Odessa, encapsulating a time of anti-religious fervor and familial bitterness; a Georgian dish called Chanakhi celebrates Stalin's death and the era touted for its "totalitarian joy"; the ersatz ingredients fondly remembered in the 1970s converge happily in the Salat Olivier, smothered with the ubiquitous Soviet mayonnaise Provansal. With anecdotes, history and recipes, the author delivers a lively, precisely detailed cultural chronicle. With a wink and a grimace, von Bremzen vividly characterizes the "Homo sovieticus."

COPYRIGHT(2013) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

September 15, 2013

While the title suggests a massive volume of recipes, this work is actually a memoir of life in Soviet Russia. The book is subdivided by decade, and von Bremzen (contributing editor, Travel + Leisure; The New Spanish Table) weaves her own memories together with stories from her grandmother and mother, beginning in 1910. The common denominator--and recurring touchstone--is food. The author vividly describes foods such as the kulebiaka, a towering pastry of fish, rice, and mushrooms, and salat Olivier, a French chef's extravagant creation that underwent a Soviet reformation, swapping carrots for crayfish and chicken for grouse and putting potatoes and canned peas at the forefront before the entire dish was smothered in mass-produced mayonnaise. Von Bremzen concludes with nine recipes. VERDICT A poignant history of everyday life in Soviet Russia and the author's personal journey to the United States, this volume is more likely to appeal to history buffs looking for a personal account than to foodies seeking a guidebook. For Russian cooking, see von Bremzen's James Beard Award-winning Please to the Table: The Russian Cookbook.--Rosemarie Lewis, Georgetown Cty. Lib., SC

Copyright 2013 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

September 15, 2013

Most Westerners imagine Stalinist Russia as a food desert: politics dictating taste, failed agricultural policies yielding shortages and famines, muddled distribution systems spawning interminable queues, and black markets supplying forbidden goods. Although this view has plenty of truth, it lacks nuance and humanity, as von Bremzen reveals so eloquently in this memoir. Arriving at age 10 in Philadelphia with her mother and a couple of suitcases, she found herself in a new culinary world that she ultimately embraced. Nevertheless, she pined for some of the great prerevolutionary Russian dishes, such as kulebiaka, the famous salmon pie that so defines classic Russian cooking. Von Bremzen, disdaining czarist Russia as much as the Soviet Union, shows the personal side of Soviet life, recounting the terror of war and secret police as well as the power of human resilience. Thanks to some recipes, American home cooks may summon up for themselves the tastes and smells the author evokes.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2013, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران