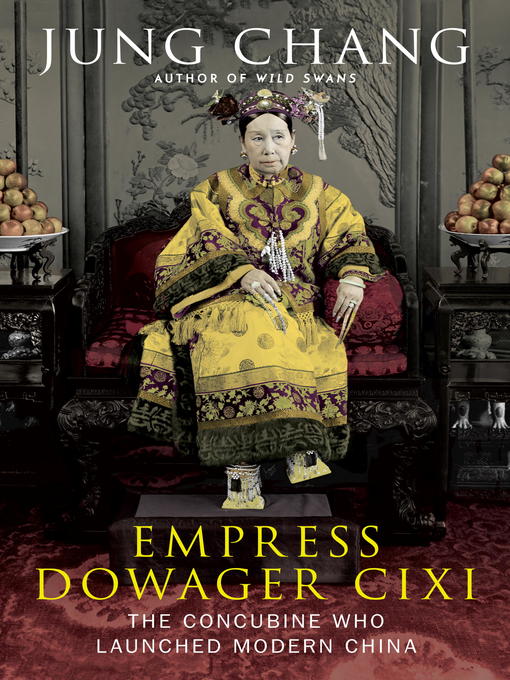

Empress Dowager Cixi

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

August 26, 2013

Her original first name was considered too inconsequential to enter in the court registry, yet she became the most powerful woman in 19th-century China. Born in 1835 to a prominent Manchu family, Cixi was chosen in 1852 by the young Chinese Emperor Xianfeng as one of his concubines. Literate, politically aware, and graceful rather than beautiful, Cixi was not Xianfeng's favorite, but she delivered his firstborn son in 1856. When the emperor died in 1861, he bequeathed his title to this son, with regents to oversee his reign. Cixi did not trust these men to competently rule China, so she conspired with Empress Zhen, her close friend and the deceased emperor's first wife, to orchestrate a coup. Memoirist Chang (Wild Swans) melds her deep knowledge of Chinese history with deft storytelling to unravel the empress dowager's behind-the-throne efforts to "Make China Strong" by developing international trade, building railroads and utilities, expanding education, and constructing a modern military. Cixi's actions and methods were at times controversial, and in 1898 she thwarted an assassination attempt sanctioned by Emperor Guangxu, her adopted son. Cixi's power only increased after this, and she finally exacted revenge on Guangxu just before her death in 1908. Illus.

September 15, 2013

An impassioned defense of the daughter of a government employee who finagled her way to becoming the long-reigning empress dowager, feminist and reformer. Chang (Wild Swans: The Daughters of China, 1991) strongly argues for a fresh look at this much-maligned monarch, who presided over China at a challenging period, when it was on the cusp of modernization and foreign invasion. Chosen as one of several concubines for the teenage Emperor Xianfeng in 1852, 16-year-old Cixi possessed more poise than beauty and was used to asserting her will in her own family; her star rose when she gave birth to the emperor's first son. A shrewd observer of the failed policy of trying to block Western influence in China, Cixi believed shutting out the enemy only brought catastrophe for the empire. After engineering the coup in 1861 that defeated the regents, effectively installing the two dowager empresses to power, Cixi ushered in a new era in the expansion of foreign trade centered in Shanghai and the buildup of a modern navy and arms industry. She welcomed foreigners and sent emissaries to tour Europe to report back on the outside world for the first time. The short-lived reign of her son Tongzhi, who died in 1875, meant that she continued on the throne, installing her sister's son, Guangxu, as her adopted son, so that her popular modernization policy continued--e.g., the beginning of coal mining and the installation of electricity. The coming-of-age of Emperor Guangxu meant the retirement of Cixi and a heap of foreign humiliation on the country, starting with the war with Japan. Yet this tenacious empress rebounded from an assassination plot and exile to implement a series of remarkable reforms in the six years before her death in 1908. In an entertaining biography, the empress finally has her day.

COPYRIGHT(2013) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

October 15, 2013

Chang, author of the impeccable Wild Swans (2003), provides a revisionist biography of a controversial concubine who rose through the ranks to become a long-reigning, power- wielding dowager empress during the delicate era when China emerged from its isolationist cocoon to become a legitimate player on the international stage. As Cixi's power and influence grewshe actually helped orchestrate the coup of 1861 that led directly to her own dominion as regentshe radically shifted official attitudes toward Western thoughts, ideas, trade, and technology. Ushering in a new era of openness, she not only brought medieval China into the modern age, but she also served double duty as a feminist champion and icon. When an author as thorough, gifted, and immersed in Chinese culture as Chang writes, both scholars and general readers take notice.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2013, American Library Association.)

June 1, 2013

First a Red Guard, then the recipient of a doctoral degree in linguistics from England's Bristol University, then the hugely best-selling author of Wild Swans and Mao, Chang has a remarkable life story. Her subject here is even more remarkable. Made a concubine at age 12, Cixi gave birth to Emperor Xianfeng's only male heir and had herself appointed regent when he succeeded to the throne as a four-year-old in 1861. When he died, she had a young nephew appointed emperor and continued what many consider an enlightened reign until her death in 1908.

Copyright 2013 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

Starred review from September 1, 2013

Was Cixi (1835-1908) the "most evil woman in Chinese history"? In 1861, she began more than four decades of power as the mother of the young new emperor--hence the title Empress Dowager. She ruled first in her son's name, then, despite dynastic regulations prohibiting women from holding power, controlled the government "from behind the throne" for the rest of her life. After Cixi's death, Chinese and Western historians unfairly blamed her for every mistake and defeat that led to the fall of the Manchu Qing dynasty in 1911. In the 1970s, however, careful scholars began to call her the "much maligned" empress dowager and questioned the accounts created by her political enemies. Chang (Mao: The Unknown Story) extends to the empress dowager the charitable sympathy that she denied Mao. She uses the work of revisionist scholars to paint a largely plausible portrait of a ruthless, farsighted politician who welcomed change and restructured the state. Chang less convincingly paints Cixi as a feminist and a liberal modernizer; Cixi "launched modern China" only if by "modern China" you mean the state dictatorships of Chiang Kai-shek, Mao, and Deng Xiaoping. VERDICT A fascinating and instructive biography for anyone interested in how today's China began. [See Prepub Alert, 5/13/13.]--Charles Hayford, Evanston, IL

Copyright 2013 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

September 1, 2013

Was Cixi (1835-1908) the "most evil woman in Chinese history"? In 1861, she began more than four decades of power as the mother of the young new emperor--hence the title Empress Dowager. She ruled first in her son's name, then, despite dynastic regulations prohibiting women from holding power, controlled the government "from behind the throne" for the rest of her life. After Cixi's death, Chinese and Western historians unfairly blamed her for every mistake and defeat that led to the fall of the Manchu Qing dynasty in 1911. In the 1970s, however, careful scholars began to call her the "much maligned" empress dowager and questioned the accounts created by her political enemies. Chang (Mao: The Unknown Story) extends to the empress dowager the charitable sympathy that she denied Mao. She uses the work of revisionist scholars to paint a largely plausible portrait of a ruthless, farsighted politician who welcomed change and restructured the state. Chang less convincingly paints Cixi as a feminist and a liberal modernizer; Cixi "launched modern China" only if by "modern China" you mean the state dictatorships of Chiang Kai-shek, Mao, and Deng Xiaoping. VERDICT A fascinating and instructive biography for anyone interested in how today's China began. [See Prepub Alert, 5/13/13.]--Charles Hayford, Evanston, IL

Copyright 2013 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران