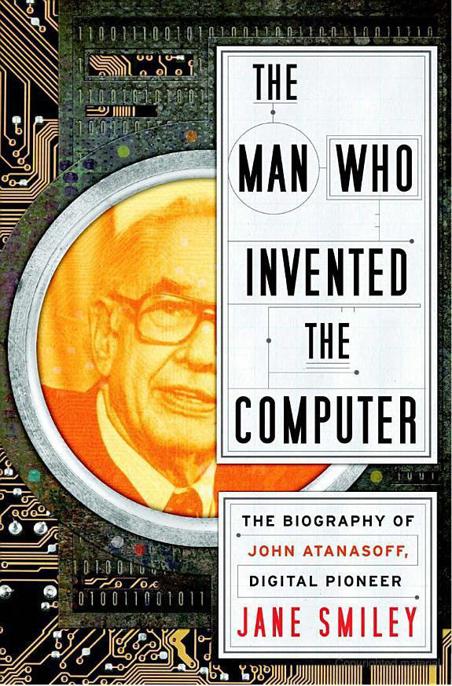

The Man Who Invented the Computer

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

September 13, 2010

Novelist Smiley explores the story of the now mostly forgotten Atanasoff, a brilliant and engaged physicist and engineer who first dreamed of and built a computational machine that was the prototype for the computer. With her dazzling storytelling, Smiley narrates the tale of a driven young Iowa State University physics professor searching for a way to improve the speed and accuracy of mathematical calculations. In 1936, Atanasoff and his colleague, A.E. Brandt, modified an IBM tabulator—which used punched cards to add or subtract values represented by the holes in the cards—to get it to perform in a better, faster, and more accurate way. One December evening in 1937, Atanasoff, still struggling to hit upon a formula that would allow a machine to replicate the human brain, drove from Ames, Iowa, to Rock Island, Ill., where, over a bourbon and soda in a roadside tavern, he sketched his ideas for a machine that would become the computer. As with many scientific discoveries or inventions, however, the original genius behind the innovation is often obscured by later, more aggressive, and savvy scientists who covet the honor for themselves. Smiley weaves the stories of other claimants to the computer throne (Turing and von Neumann, among others) into Atanasoff's narrative, throwing into relief his own achievements.

September 1, 2010

Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Smiley (Private Life, 2010, etc.) looks at the curious personalities and tortured paths that led to the first computer(s).

As in her novels, the author displays a talent for keeping a dozen fully realized characters on stage. While John Atanasoff is certainly a likely candidate for "the man who invented the computer," plenty of strange, captivating people were concurrently at play in the same field. "The story of the invention of the computer," writes Smiley, "is a story of how a general need is met by idiosyncratic minds, a story of how a thing that exists is a thing that could have easily existed in another way, or, indeed, not existed at all." But it did exist, and in permutations galore, the brainchildren of a host of atypical men: geniuses, cranks, the impossibly remote, the backroom dealer. The author provides vivid characterizations of each: Atanasoff, enterprising, hardworking and so highly directed that he could have been an Asperger's candidate; Alan Turing, a computer visionary who couldn't build a birdhouse; Konrad Zuse, a German reduced to scavenging pieces of material for his machine from the bombed-out streets of Berlin "without getting shot for looting"; John von Neumann, who contributed important architectural features to computer design and whose upper-class connections allowed him great freedom. Smiley captures the men in their evolving milieus—at universities and in war rooms and business offices—and notes that they sometimes came into contact. One example was the meeting between Atanasoff and John Mauchly, another computer designer, a brief encounter in which Atanasoff revealed the workings of his machine, and ultimately led to the patent case that was found in Atanasoff's favor as the inventor of the first "automatic electronic digital computer for solving large systems of simultaneous linear equations."

Engrossing. Smiley takes science history and injects it with a touch of noir and an exciting clash of vanities.

(COPYRIGHT (2010) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

September 15, 2010

Several popular works have dealt with the question of who invented the computer, and novelist Smiley has obviously read and deeply pondered them all. She emerges from her immersion in binary arithmetic, vacuum tubes, and eccentric geniuses with a scintillating narrative synthesis that agrees with the prevailing technical opinion (Who Invented the Computer? by Alice Burks, 2003) that John Atanasoff, a mechanical fiddler extraordinaire, had the first computer functioning by 1941. But off the beaten path in Ames, Iowa, it attracted little notice after its builder diverted into war work, as did another physicist who had seen Atanasoffs machine: John Mauchly, whose idea-sprouting indiscipline Smiley draws as vividly as she does Atanasoffs cantankerous technical tenacity. Mauchly was central to the construction of ENIAC, once considered the first computer. Did he filch Atanasoffs ideas, asked litigation in the 1970s? Before arriving at the courthouse, Smiley integrates into the story profiles of the computer theorists and builders of the 1940s, including Alan Turing, John von Neumann, and Konrad Zuse. Told with self-propelling fluidity, Smileys fine account will certainly draw more than the technophile base due to her literary cachet. HIGH-DEMAND BACKSTORY: This biography written by acclaimed novelist Jane Smiley is the first entry in Doubledays Great Innovators series.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2010, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران