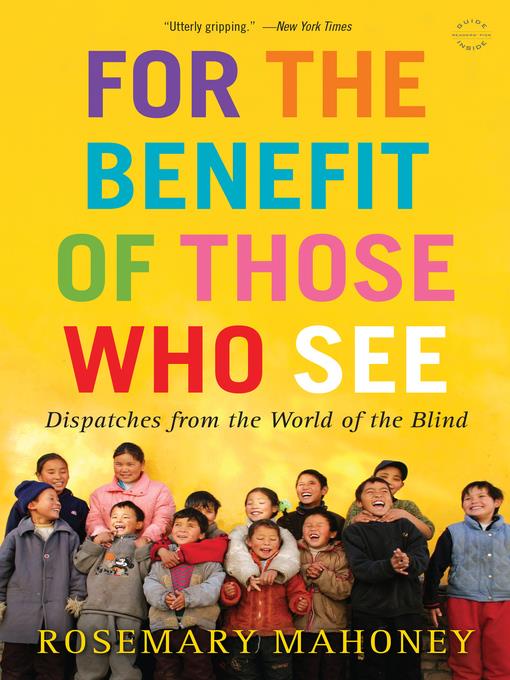

For the Benefit of Those Who See

Dispatches from the World of the Blind

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

October 28, 2013

“The blind can well enough defend themselves,” says Mahoney (Down the Nile) in this beautiful book about a vibrant leader of the blind, Sabriye Tenberken. German-born Tenberken founded a school for blind children in Tibet—which later became Braille Without Borders—as well as a school in Kerala, India, to train blind teachers. Mahoney, who is sighted, became a teacher at the latter facility and was at first terrified by her decision. All around her, the blind were laughing, thinking, walking without fear and with an impossible patience. She was startled by the way her students easily inhabited “a world dominated by thought rather than appearances.” Doubting herself, she says, “I was not even a well-adjusted sighted person... I was born impatient and annoyed.” For such reasons, she writes, “I was not quite sure I was prepared to teach.” She stumbles through her first challenge—to define “twinkling”—as one might expect of a sighted person in a sightless world. But in time Mahoney becomes an exceptional translator for the blind, mediating for what she ends up seeing as two groups of the sighted: those who see with their eyes, and those who see with their minds. Agent: Betsy Lerner; Dunow, Carlson & Lerner Literary Agency.

Starred review from November 1, 2013

A spiritual odyssey into the world of the blind. In 2005, Mahoney (Down the Nile Alone: In a Fisherman's Skiff, 2007, etc.) visited Braille Without Borders, Tibet's first school for the blind, founded by German educator Sabriye Tenberken, who herself is blind. It offered classes in "Braille, Chinese, English, computers, mathematics and navigational skills," to blind young Tibetans, many of whom were illiterate and had been living in deplorable conditions in their impoverished villages, where they were a burden to their families and were shunned and bullied by their peers. At first, the author viewed the trip with trepidation, believing the typical stereotype that the blind were deprived of "their real enjoyment of life, their effectuality, and their potential." Mahoney was astonished to see the students' levels of joy and accomplishment. Being blind, many of them said, had given them the opportunity to leave the hardscrabble existence in their villages and attend this wonderful school where they were being educated and making new friends. For the author, the experience was a revelation. Four years later, she volunteered to teach English at a new school that Braille Without Borders was opening in India, attended by adult students from Africa and Latin America as well as Asia who wished to work on behalf of the blind in their own countries. The diversity of the students greatly enhanced the vibrancy of the community, and Mahoney was impressed by their intellectual and spiritual depths. She observed that they navigated the heavily trafficked streets of Kerala with ease. They gathered information about their environment from their other senses in order to recognize people and places, and they lived in a world "dominated by thought rather than appearance and visual details." After all, she writes, "it's the ability to reason and communicate that make us extraordinary." A beautiful meditation on human nature.

COPYRIGHT(2013) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

December 1, 2013

Like many sighted people, Mahoney (Down the Nile: Alone in a Fisherman's Skiff) dreaded the idea of going blind and felt uncomfortable around blind people. A magazine assignment sent her to visit Braille Without Borders, Tibet's first educational institution for the blind, and its founder, blind German educator Sabriye Tenberken. Mahoney's encounters with Tenberken and her resilient students inspired her to take a teaching position at Tenberken's International Institute for Social Entrepreneurs (IISE) in Kerala, India, which trains and empowers visually impaired adults. Here she surveys the history of blind education and the surprising, upsetting results of vision restoration surgery but also focuses on the Tibetan children and the IISE students from lands as diverse as Liberia, Japan, and Norway. Readers learn shocking backstories relating to prejudices and ignorance that led to neglect and abuse of blind people--from children kept in permanent confinement to the harvesting of body parts of blind African albinos. Yet in the context of the joy, determination, and dignity of the tellers here, Mahoney's overall story is one of hope and affirmation. VERDICT This gracious book illuminates blind culture and teaches something of lifeways in Tibet, southern India, and sub-Saharan Africa. It should reach a wide general audience and may also bring readers to Tenberken's own work, My Path Leads to Tibet.--Janet Ingraham Dwyer, State Lib. of Ohio, Columbus

Copyright 2013 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران