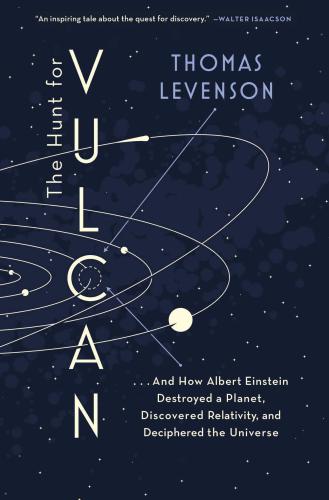

The Hunt for Vulcan

. . . And How Albert Einstein Destroyed a Planet, Discovered Relativity, and Deciphered the Universe

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

August 17, 2015

The history of science brims with searches for mysteries that didn’t pan out, and Levenson (Newton and the Counterfeiter), director of the graduate program in science writing at MIT, charmingly captures the highs and lows of one such hunt—for the “undiscovered” planet Vulcan in the 19th century. Levenson explains that Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity gave astronomers of the period the expectation that orbiting bodies move along predictable elliptical paths; according to the theory, a wobble in a planet’s orbit would hint that the gravity of another body is affecting it. Neptune was discovered in the mid-19th century after irregularities were observed in the orbit of Uranus, so when perturbations were observed in Mercury’s orbit, a “planet fever” sent astronomers hunting for something orbiting nearby, close to the Sun. Levenson captures both the hunt and hunters in broad, lively strokes, including the grumpy Urbain Le Verrier, “a man who cataloged slights, tallied enemies, and held his grudges close,” and Edmond Lescarbault, a doctor and do-it-yourself “village astronomer.” Arguments over orbital mechanics and planet-shaped shadows (which turned out to be sunspots) in solar photos ended in 1915 with Einstein’s general theory of relativity and its description of curved space-time, which explained Mercury’s wobble. Levenson deftly draws readers into a quest that shows how scientists think and argue, as well as how science advances: one discovery at a time. Agent: Eric Lupfer, William Morris Endeavor.

Starred review from September 15, 2015

Levenson (Science Writing/MIT; Newton and the Counterfeiter: The Unknown Detective Career of the World's Greatest Scientist, 2009, etc.) connects Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity to Isaac Newton's Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. In their day, each provided "a radical new picture of gravity" that ultimately depended on astronomical confirmation. For Newton, his moment of truth occurred in 1687, when he established the universality of the inverse-square law of gravitation that governed the elliptical orbits of the planets. He showed that it also applied to the path of the major comet of 1680. "It was cosmic proof," writes Levenson, "that the same laws that governed ordinary experience-the apple's fall, an arrow's flight, the moon's constant path-ruled all experience, to the limits of the universe." Newton based his theory on the estimated distance from the sun to the then-known planets. Pierre-Simon Laplace extended Newton's theory to account for the orbital perturbations caused by interactions between neighboring planets such as Jupiter and Saturn. Similar calculations allowed astronomers to predict the existence of Neptune based on discrepancies in the elliptical orbit of Uranus. The case of Mercury was more puzzling because its divergence from an ellipse could not be accounted for by the gravitational pull of neighboring Venus. Scientists entertained the spurious hypothesis of the existence of a heretofore-unobserved planet orbiting the sun, which they named Vulcan. Einstein solved the dilemma by replacing Newton's inverse-square law with his theory of general relativity, a complicated mathematical theory based on a simple geometrical image of "the sun with its great mass, creat[ing] a bulge in space time." Rather than action-at-a-distance, he introduced the curvature of space-time as a medium for the propagation of gravity. This allowed him to make a more precise prediction of Mercury's orbit, which was verified in 1917 by observations made during a solar eclipse. Though brief, Levenson's narrative is a well-structured, fast-paced example of exemplary science writing. A scintillating popular account of the interplay between mathematical physics and astronomical observations.

COPYRIGHT(2015) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

September 1, 2015

For more than 60 years before 1915, scientists searched for Vulcan, a missing planet whose gravitational pull could explain Mercury's orbit. In 1915, however, when Einstein announced his theory of general relativity, the search was over, as his work proved that no such planet existed or ever had. Levenson (science writing; director, graduate program in science writing, MIT) covers from Edmond Halley's research in 1600s England to the World War I era to describe forerunners to Einstein, the genuis's innovations, and the implications of his theory to cosmology.

Copyright 2015 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران