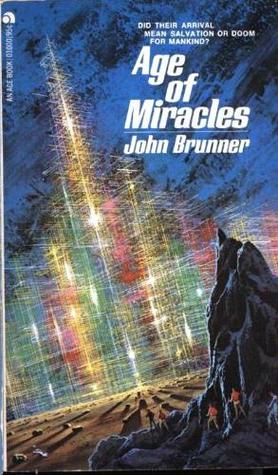

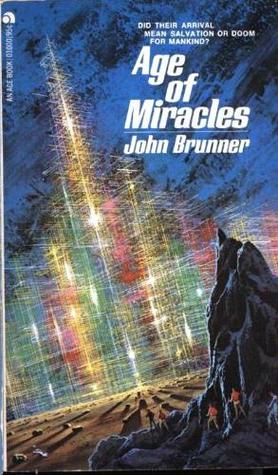

Age of Miracles

از خودتان درباره کتاب توضیح کوتاهی بنویسید

In Age of Miracles Brunner confronts his characters with an alien transportation system produced by unknown creatures clearly superior in knowledge & application of science. While human characters do learn to make some limited use of the system, their position at the end is comparable to that of rats on a sea-going ship, &, as the characters themselves indicate, their future use of the network is predicated on just how annoying these human rats become to the aliens: "...since we quit pilfering live artefacts, the aliens have shown no sign of noticing us. I suspect they can't be bothered. We've put up with rats & mice for thousands of years, & we only take steps against them when they cause great harm" (Ch28).

لغو

ذخیره و ثبت ترجمه

دیدگاه کاربران