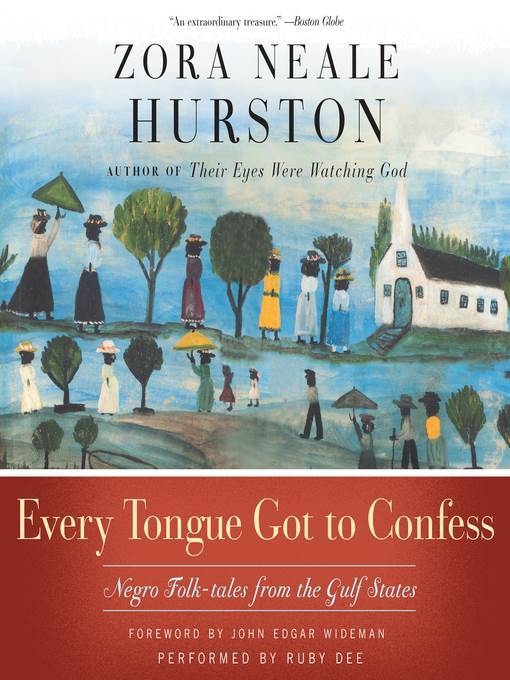

Every Tongue Got to Confess

Negro Folktales from the Gulf States

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Traveling alone through the southern United States in the early part of the twentieth century, Barnard scholar Zora Neale Hurston meticulously collected the stories and anecdotes told by this country's African Americans. Her work, recorded word by word in transcripts, lay largely unpublished for decades. Now Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis bring it to life in a stunning audio production that captures the richness of the language as well as the culture behind the stories. Listening to their performance is like listening to the original story-tellers sharing "lies" with friends on a warm summer evening. Given the spoken nature of folklore, theexcellent audio rendition can only improve on the original written publication. A foreword by John Edgar Wideman and an introduction by Carla Kaplan provide fascinating insight into both the collection and the recording of the stories, as well as their place in African-American history. A cultural treasure. R.P.L. 2003 Audie Award Finalist (c) AudioFile 2002, Portland, Maine

December 17, 2001

Although Hurston is better known for her novels, particularly Their Eyes Were Watching God, she might have been prouder of her anthropological field work. In 1927, with the support of Franz Boas, the dean of American anthropologists, Hurston traveled the Deep South collecting stories from black laborers, farmers, craftsmen and idlers. These tales featured a cast of characters made famous in Joel Chandler Harris's bowdlerized Uncle Remus

versions, including John (related, no doubt, to High John the Conqueror), Brer Fox and various slaves. But for Hurston these stories were more than entertainments; they represented a utopia created to offset the sometimes unbearable pressures of disenfranchisement: "Brer Fox, Brer Deer, Brer 'Gator, Brer Dawg, Brer Rabbit, Ole Massa and his wife were walking the earth like natural men way back in the days when God himself was on the ground and men could talk with him." Hurston's notes, which somehow got lost, were recently rediscovered in someone else's papers at the Smithsonian. Divided into 15 categories ("Woman Tales," "Neatest Trick Tales," etc.), the stories as she jotted them down range from mere jokes of a few paragraphs to three-page episodes. Many are set "in slavery time," with "massa" portrayed as an often-gulled, but always potentially punitive, presence. There are a variety of "how come" and trickster stories, written in dialect. Acting the part of the good anthropologist, Hurston is scrupulously impersonal, and, as a result, the tales bear few traces of her inimitable voice, unlike Tell My Horse, her classic study of Haitian voodoo. Though this may limit the book's appeal among general readers, it is a boon for Hurston scholars and may, as Kaplan says in her introduction, establish Hurston's importance as an African-American folklorist. (Dec.)Forecast:Hurston's name will ensure this title ample review coverage, and it should do well among lovers of folktales, particularly those curious about Hurston's career in the field.

June 15, 2002

Folklorist Hurston, who died in 1960, collected these stories in the late 1920s from African Americans in the rural South. The tales range from one liners to more complex stories, divided by subject: God tales, neatest trick tales, preacher tales, devil tales, and so on. Hurston replicates the vernacular in which these were told. In this recorded version, Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis perform and are able to include the often sly, often sparkling wit of the original tellers. A real treat for students of folklore, black culture, or anyone who likes hearing good stories well-told. Nann Blaine Hilyard, Lake Villa Dist. Lib., IL

Copyright 2002 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

October 1, 2001

Hurston's deep fascination with story, language, and African American culture inspired her to become a folklorist, anthropologist, novelist, and memoirist in an age when black women were considered second-class citizens at best, and African American literature was segregated from the canon. When she died poor and forgotten in 1960, the lion's share of her papers were misplaced, including nearly 500 of the black folktales she collected while driving solo across the South in the 1920s. Published here for the first time, these rescued folktales are introduced by Carla Kaplan, who explains that Hurston had planned a seven-volume folktale series but was only able to publish two, " Mules and Men" (1935) and" Tell My "Horse (1938). In this catch-up collection, it's obvious that Hurston transcribed each tale with great care, intent on preserving both the sound and sense of this unique vernacular oral tradition. In his frank and penetrating foreword, John Edgar Wideman discusses the prickly question of how dialect enforces racial stereotypes, but clearly Hurston sought to capture the "folk voice" of the South out of deep respect for its canny inventiveness, subversive humor, and immeasurable impact on the American character. And what treasures these are--mordantly clever and quintessentially human stories about God and the creation of the black race, the devil, preachers wily and foolish, animals, the battle between the sexes, and slaves who outsmart their masters. Invaluable tales of mischief and wisdom, spirit and hope.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2001, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران