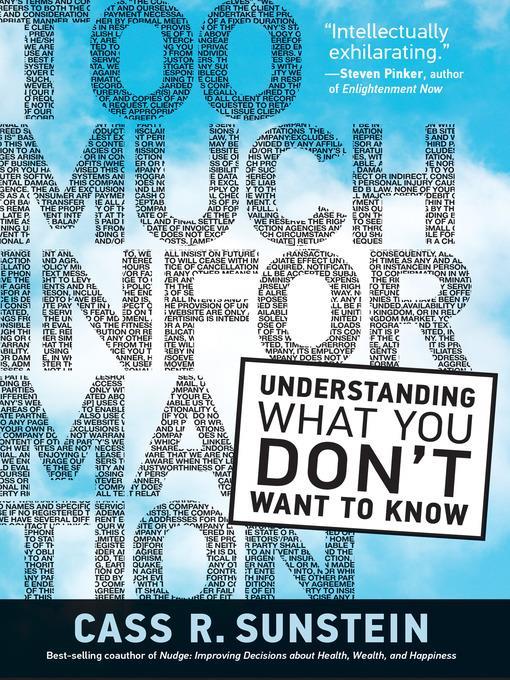

Too Much Information

Understanding What You Don't Want to Know

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

May 25, 2020

Harvard Law School professor Sunstein (Conformity) considers the legal, social, and psychological implications of government-mandated information disclosures in this nuanced account. Contending that nutrition labels, restaurant menu calorie counts, credit card bill late fees, and other mandated disclosures should be evaluated on whether they “increase human well-being,” rather than simply provided as part of the public’s “right to know,” Sunstein parses the “hedonic value,” or pleasure, people take in knowing—or not knowing—something, and the “instrumental value” people assign to information based on how they can use it. He compiles data on consumers’ “willingness to pay” for tire safety rankings and the potential side effects of pain medication; contends that the positive and negative feelings associated with such disclosures should be given more weight than they currently are; and outlines potential benefits and limitations to a system of “personalized disclosure,”in which the government mandates certain basic information, but makes further details available to those who want it through apps and other technologies. Readers with a background in the social sciences and moral philosophy will have an easier time engaging than generalists, though Sunstein writes in clear, accessible language throughout. This balanced and well-informed take illuminates an obscure but significant corner of government policy making.

July 1, 2020

A former presidential adviser considers the complexities of information disclosure. Sunstein, a legal scholar who, in the Obama White House, oversaw federal regulations that required disclosure about such matters as nutrition and workplace safety, opens his latest book by asking, "When should government require companies, employers, hospitals, and others to disclose information?" His short answer: whenever doing so makes people happier or helps them make decisions. But as he notes, "Whether it's right to disclose bad news depends on the people and the situation. One size does not fit all." In these essays, Sunstein addresses key questions policymakers should consider when deciding whether to disclose or request information. Topics include the reasons people might or might not want information (a friend joked that he "ruined popcorn" after the FDA finalized a regulation that movie theaters and restaurants had to disclose caloric content); the psychological factors to consider when designing disclosures, such as that some people don't read them, especially when, as with software downloads, they're long; and the value people place on social media, an essay in which he notes a paradox: "the use of Facebook makes people, on average, a bit less happy--more likely to be depressed, more likely to be anxious, less satisfied with their lives," yet many people "would demand a lot of money to give it up." Despite the use of jargon such as "hedonic loss" and "availability heuristics," the narrative is clear and relatable. Sunstein even delivers a few zingers, as when he notes in the chapter on "sludge," the term for the excessive paperwork people wade through to cancel magazine subscriptions or sign up for free school meals: "The Department of the Treasury, and the IRS in particular, win Olympic gold for sludge production." An accessible treatise on the need to ensure that information improves citizens' well-being.

COPYRIGHT(2020) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

دیدگاه کاربران