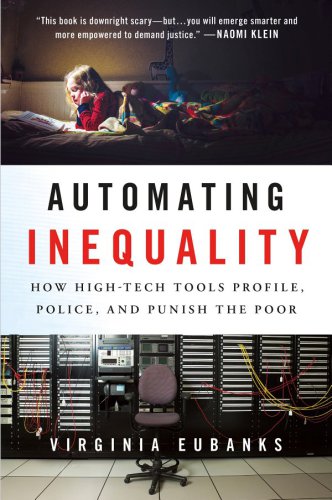

Automating Inequality

How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

November 1, 2017

Algorithms, predictive models, regression analyses: all are tools for criminalizing the poor and immiserating the middle class.In 2015, Eubanks (Political Science/Univ. at Albany, SUNY; Digital Dead End: Fighting for Social Justice in the Information Age, 2011, etc.) writes by way of scene-setting, a series of computer-generated decisions cast doubt on a medical claim she was filing, flagging it as potential fraud. It took significant time and effort to clear her name, and she was a person with the education and standing needed to confront the system. Most Americans are not so well-equipped, and all face the same system, which removes ordinary decisions from human decision-makers and puts them in the purview of machines--as well as algorithms and rules that are largely intended to maximize the profits of the increasingly privatized providers of social services and to deny those in need of precisely those services in the first place. All Americans, from the poor to the wealthy, are implicated in this system. "We have all always lived in the world we built for the poor," writes Eubanks, and thus should not be surprised when we are cast out when we become sick, disabled, elderly, or otherwise in need of the social safety net that so many politicians, at the national and state levels, are bent on removing. The author's examination of the technological system underlying this dismantling is sobering. By her account, there seems to be little rhyme or reason to how cities such as Los Angeles determine who receives public housing, but there does seem to be a rationale behind Indiana's propensity for losing welfare-related paperwork and thus denying "more than a million applications for food stamps, Medicaid, and cash benefits, a 54 percent increase compared to the three years prior to automation."Equal parts advocacy and analysis--a welcome addition to the growing literature around the politics of welfare.

COPYRIGHT(2017) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

February 1, 2018

Using story after devastating story, Eubanks (women's studies; Univ. at Albany, State Univ. of New York; Digital Dead End: Fighting for Social Justice in the Information Age) provides a tour of the algorithms, data mining practices, and predictive risk models that increasingly (and often arbitrarily) target poor and working-class Americans for scrutiny and punishment. Big data systems (often operated for profit by the private sector) are sold to local governments as neutral, efficient replacements for human decision-makers but have the effect of diverting services from and criminalizing the poor. Eubanks's advocacy for the Americans impacted by this trend is passionate and matched by incisive analysis and bolstered by impressive research. VERDICT An important contribution to the growing literature sounding the alarm on the consequences of automating social policy and the dangers of big data. Eubanks's writing is clear and approachable and her use of narrative will appeal to general readers while being essential for policymakers and academics.--Rachel Bridgewater, Portland Community Coll. Lib., OR

Copyright 2018 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

Starred review from December 15, 2017

Recognizing the direct link between the poorhouses of U.S. history and contemporary automated systems that re-create poorhouse conditions, Eubanks (Digital Dead End, 2012) dives deeply into three examples. Indiana lawmakers signed a $1.3 billion dollar contract to privatize and automate welfare, in part to reduce the fraud and waste they believed rampant. The system divorced recipients from trained caseworkers and caused eligible people in genuine need to suffer the erroneous cancellation of benefits. Residents of L.A.'s Skid Row are matched with increasingly limited housing resources by an automated system. To be eligible, unhoused people must receive a score by volunteering their most intimate data: mental health, physical health, sexual-assault history, domestic-violence history, etc. In Pittsburgh, scores predict if children will experience abuse or neglect in the future, yet the system encodes cultural and racial biases. People who must use these automated systems learn to expect little and object less for fear of being marked noncompliant. Eubanks argues that automated systems separate people from resources, classify and criminalize people, and invade privacyand that these problems will affect everyone eventually, not just the poor. The book's final chapter offers strategies to dismantle the digital poorhouse.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2017, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران