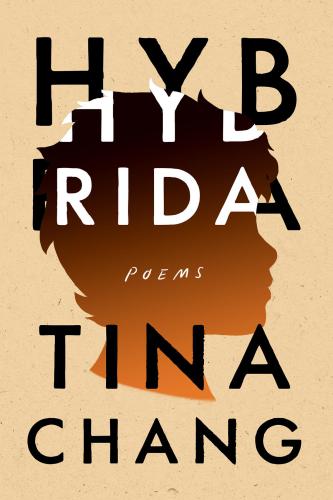

Hybrida

Poems

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

May 1, 2019

As its title poem suggests, this new collection from Brooklyn poet laureate Chang (Of Gods and Strangers) is itself a hybrid consisting of variations of haiku, ekphrastic poems, free verse, list poems, sonnets, ghazels, prose poems, and terza rima. Here, Chang draws from her own experiences, stories from the Bible, fairy tales, and contemporary news accounts, as well as from other poets. The poem "276," for example, refers both to Gerard Manley Hopkins's poem "The Windhover" and several reports about the kidnapping of Nigerian school girls. In many of these pieces, Chang worries about the safety of her son and especially his future as he grows to manhood. She also muses on African American youth such as Michael Brown, who are unfairly treated by law enforcement, with the implied message that her son, too, could be harmed. Although some poems seem too politicized, it helps that Chang writes with a wonderful sense of metaphor, as in "my son senses what is happening/ on the street, his heart fiercely tethered/ to mine" or "hair rushing to the waist like ink." VERDICT A mysterious I-narrator speaks, whispers, and sometimes hisses these intense, urgent poems, which ultimately form a lament. For academic holdings and public collections that include a political or own voices element.--C. Diane Scharper, Towson Univ., MD

Copyright 2019 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

Starred review from May 20, 2019

The title of Chang’s third collection signals a fusion of disparate elements, a hybrid that’s been seemingly feminized. This mélange appears across an impressive array of forms: prose poems, ghazals, responses to artworks (by Alexandria Smith and Kara Walker, for example), the several-page “Bitch” and “Creation Myth,” as well as verse that explores Chang’s personal history. Primarily, though, this is a book about the speaker’s son: her love for him, and how she and he negotiate his blackness in the world. In the opening poem, “He, Pronoun,” she writes: “I have a right to fear for him,// though I have no right to claim his color./ His blackness is his to own and what will// my mouth say of that sweetness.” The poem closes on the image of her son in her lap, a quotidian moment, but they “watch the door.” With more urgency than a news article could achieve, Chang conveys the fear and rage at the reality that the color of her son’s skin will mean she is unable to keep him safe. The title poem, subtitled “a zuihitsu,” is a collage of questions and observations about identity, which at its end suggests hope for the future: “Wilderness/ of the mind. But it’s changing.”

دیدگاه کاربران