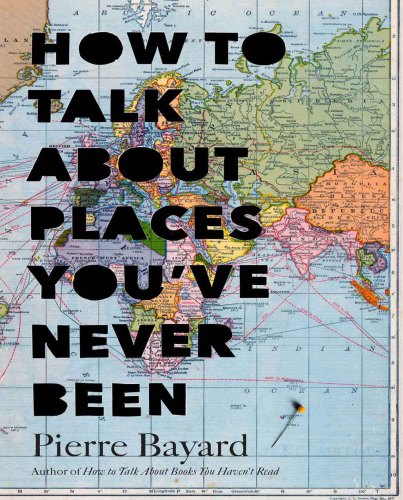

How to Talk About Places You've Never Been

On the Importance of Armchair Travel

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

December 1, 2015

In his prolog, psychoanalyst Bayard (French literature, Univ. of Paris; How To Talk About Books You Haven't Read) puts forth that "There is actually nothing to show that traveling is the best way to discover a town or a country you do not know," and later asserts that "total ignorance of a subject need not necessarily prove a handicap to an appropriate discussion about it." The volume, which the publisher bills as reference, is divided into three parts. The first identifies various ways in which writers have employed nontravel (Bayard refers to this as nonjourney); the second considers times when we might need to talk about places we've never been; and the third offers advice for the general nontraveler. This sort of preparation to engage with others about places one has never been may be meant to cultivate creativity--it's certainly understandable that a writer would need to research geography, history, and culture. However, the intention of this book is a little confusing to this reviewer. The ideas presented are no doubt intriguing but may be more enjoyable as a concise essay. VERDICT For fans of and libraries collecting the works of Bayard, as well as possibly academic armchair travelers and travel writers.--Lura Sanborn, St. Paul's Sch. Lib., Concord, NH

Copyright 2015 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

September 7, 2015

Continuing in the same vein as 2007’s How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read, Bayard, a professor of French literature at the University of Paris, constructs a case for the sedentary voyager who travels the world by neither land, air, nor water but rather by book, favoring poetic license above actual experience. This thread leads through Marco Polo’s professed encounters with unicorns and griffins in medieval Asia, Margaret Mead’s lascivious descriptions of Samoan sexual proclivities, and George Psalmanazar’s whole-cloth invention of an island society that captured the collective imagination of 18th-century Europe. Phileas Fogg, the protagonist in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, is celebrated for his expediency and emotional detachment on his trip around the world. Bayard defends German writer Karl May’s depiction of an American Old West he never visited, because it allowed for a more sensitive portrayal of Native Americans; and he feels that French poet Blaise Cendrars’s linguistic gifts bring readers aboard the Trans-Siberian Express “in the context of a shared fantasy.” Bayard puts forth some interesting ideas about the capacity of literature to take readers to other worlds and the possible superiority of these experiences to physical travel; at the very least, these notions will sit well with academics and shut-ins.

October 1, 2015

Using historical anecdotes and contrarian rhetoric, psychoanalyst Bayard (French Literature/Univ. of Paris 8; Sherlock Holmes Was Wrong: Reopening the Case of The Hound of the Baskervilles, 2008, etc.) argues that physical travel is unnecessary, and even inadvisable, when trying to understand faraway places.Throughout the book, the author celebrates the "armchair traveler," but he defines this person in several different ways. Bayard does not believe that Marco Polo actually traveled to China but instead stayed near medieval Venice and collected the stories of real travelers. Iconoclastic to the end, he criticizes the anthropologist Margaret Mead for failing to understand the Samoans she met firsthand, yet he praises Immanuel Kant for inventing modern philosophy without leaving his hometown. Bayard is fond of Phileas Fogg, the Jules Verne character who circled the globe but barely interacted with any part of it. Perhaps the book loses something in the translation, but Bayard makes few discernible points except that he doesn't consider travel a worthwhile endeavor. "If you are obligated in spite of everything to travel," he posits, "the best solution is to do it as quickly as possible, avoiding lingering anywhere along the way since nothing good can come of it." His position is so bizarre as to seem satirical, but if he's kidding, Bayard never winks. In the strangest chapter of all, he references the journalist Jayson Blair, who wrote about a war veteran in Texas, but the encounter was both made-up and largely plagiarized. Then he writes, "if we leave aside the moral dimension of journalistic trickery, Jayson Blair's story does pose the almost philosophic question, already latent in our previous examples, of knowing what it actually means to be in a place." Perhaps this "almost philosophic question" is almost valid and almost worth taking seriously. But in the end, the book feels like a pseudo-intellectual exercise. Bayard strives to applaud imagination and postmodern thinking, but his treatise comes off as stubbornly provincial, an overthought con game. A jumbled collection of random stories and half-baked ideas.

COPYRIGHT(2015) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

دیدگاه کاربران