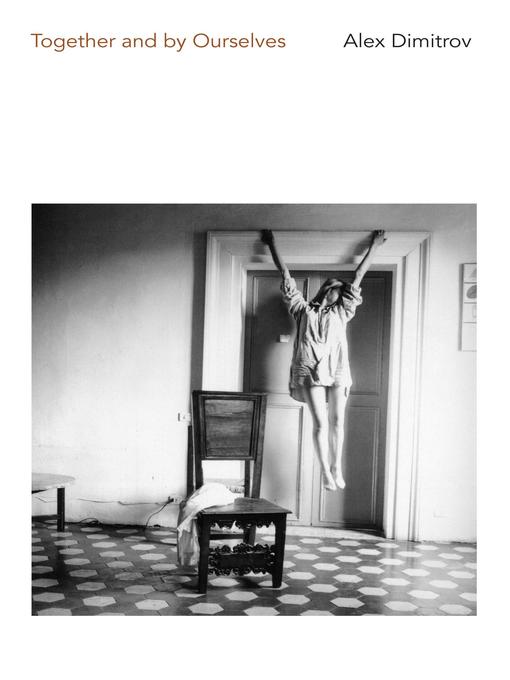

Together and by Ourselves

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

March 27, 2017

In his second collection, Dimitrov (Begging for It) negotiates the cosmopolitan as well as the cosmos through a psychopomp narrator, guiding readers—living souls—through parties and canyons and cities. The figure is reminiscent of Emerson’s transparent eyeball cruising through a cityscape or O’Hara’s observation of the world moving by: “And people walked out of churches and bars,/ cafés and apartments, cities, towns, photographs,/ someone’s Friday night party,/ someone they once knew or slept with.” Dimitrov roves through four billion years of the sun’s existence and into calendars that contain a secret 13th month. His voice is steady across poems, swiftly navigating a dizzying landscape of non sequiturs and litanies and passing faces. Many of the poems are marked by absence: “Yesterday there was nothing on the beach/ and no one knows where it came from.” The narrator’s longing inside this lack is often matched by the distance the reader feels from all these passing scenes, like being told about a memorable photograph without being permitted to look at it. In these moments the book glows. Dimitrov instills palpable emotional yearning in his readers, as if you’re a tourist inside your own life: “A little of our misplaced lives,/ we saw them waving on the roof in the dark/ and thought they were birds.”

April 15, 2017

The absence of salutations aside, Dimitrov's second collection (after Begging for It) is a series of intimate, unsent missives to an irretrievable lost love, a one-sided correspondence in which brief, fragmentary recollections of the beloved trigger a loosely woven philosophical discourse on enigmatic questions of identity and self-worth ("Is it lucky to live or embarrassing?"). Seemingly assembled one end-stopped line at a time, the collection is a series of halting, quasi stream-of-consciousness monologs ("White nothing: someone should be happy for you./ The main dish, I admit, was a little bit bloody./ That year he shortened his hair many days"), often complicated by contradiction ("The best reason to live is that there is no reason to live") and aporia ("and now that I'm happy--now what?"). The poet's existential angst is thick and unrelenting, and the world he inhabits, a ghostly, immaterial Manhattan, remains unknowable, untouchable. VERDICT Notwithstanding an occasionally apt line ("It's difficult to see the world from the world") or odd moment of self-consciousness ("This is the nineteenth line of the poem"), Dimitrov's flat diction, indifferent prosody, and unwavering tone of sober introspection grow monotonous and claustrophobic over the length of the book, diluting its emotional urgency.--Fred Muratori, Cornell Univ. Lib., Ithaca, NY

Copyright 2017 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران