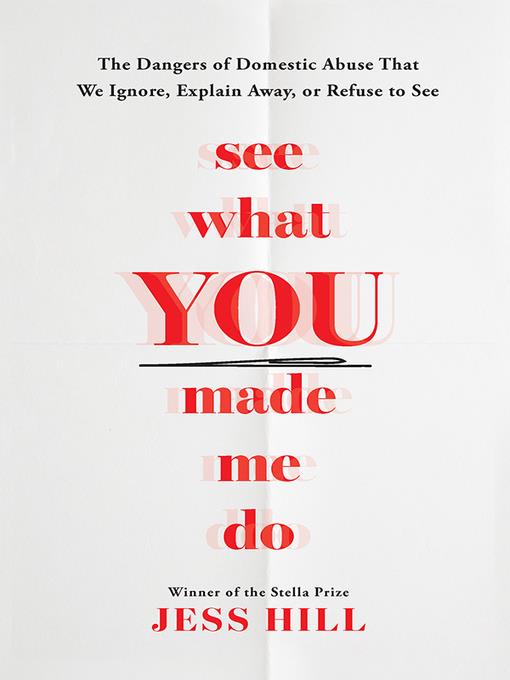

See What You Made Me Do

The Dangers of Domestic Abuse That We Ignore, Explain Away, or Refuse to See

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

August 10, 2020

Australian journalist Hill examines the individual and societal mechanisms of domestic abuse in this original and persuasive account. She compares the tactics of abusers, such as isolation, gaslighting, and surveillance, to the torture methods that led American POWs to defect to China during WWII; profiles women protecting themselves and their children from abuse they’re unable to escape; discredits victim-blaming narratives; and explains how rationalizing abuse can be a “sophisticated coping mechanism.” Hill argues that if abusers are seen as “complex humans with their own needs and sensitivities,” they can be enabled to address their “supercharged sense of entitlement” and fear of shame, and understand how the patriarchy has taught them to think about men’s power and vulnerability. Hill also examines the social and legal structures that facilitate abuse, including police inaction to domestic violence calls and courts that disregard the testimony of children. Her solutions include therapeutic models that understand an abuser’s pain but center accountability and the encouragement of community involvement in domestic violence cases. Hill’s lucid history of cultural attitudes toward domestic violence and harrowing survivor testimonies combine to powerful effect. This is a nuanced and eye-opening study of a hidden crisis.

June 15, 2020

An Australian journalist finds countless faults with how society treats those who endure domestic violence. Hill is all over the map, literally and figuratively, in this exploration of how "victims of domestic abuse have been blamed by the public, maligned by the justice system, and pathologized by psychiatrists." After winning the Stella Prize for the Australian edition, the author has revised the book heavily for the North American market, and she finds antecedents for homegrown domestic abuse in the "deeply patriarchal and deeply sexist" views of the Puritans. Hill has a wealth of insight into why women stay with abusive partners; how the police and courts fail those who have suffered; the unique vulnerabilities of Aboriginal people; and the varied types of "coercive controllers," who need more than one-size-fits-all "anger management" programs. The author also finds innovative solutions in countries including Argentina, which has special police stations for women, resembling living rooms with play spaces for children, where female victims find under one roof all the services they need--"lawyers, social workers, psychologists." Hill stumbles, however, in analyzing the U.S., most notably when she suggests that in America, as elsewhere, "2014 will likely stand as the year when the Western world finally started taking men's violence against women seriously," in part because that was the year that NFL star Ray Rice assaulted his fiancee, Janay Palmer. In fact, as Rachel Louise Snyder writes in the excellent No Visible Bruises, the U.S. watershed came two decades earlier, when "Nicole Brown Simpson became the face of a new kind of victim" and Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act. Hill's global perspective is valuable--as is a chapter on women who abuse men--but Snyder's book has a firmer grasp of the American issues. An expos� of domestic abuse that portrays other countries more convincingly than it does the U.S.

COPYRIGHT(2020) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

September 1, 2020

This is an exhaustive, horrifying, and compelling consideration of domestic abuse, in its many guises and from multiple perspectives. Unflinchingly, the text rolls out dreadful stories and mind-boggling statistics, covering decades of research and socio-psychological theories regarding abused women and their abusers. After the book's original publication in Australia, author Hill revised her material to incorporate data from the U.S. She found staggering similarities among British, Australian, and American abuse survivors. Hill explores the roles guilt and shame play in these toxic relationships, the ingrained patriarchy condemned by the #MeToo movement, sexual exploitation of Indigenous populations, and devastating material about wrongdoings inflicted on children by family courts. There are pages-long, graphic descriptions of specific situations when help was available, but was not mentioned or offered. There are some positives (successful intervention programs in Brazil and Scotland are cited), and the final chapter touts the effectiveness of community-led, local initiatives. Hill calls for cultural and social change, positing that "Revolutions are impossible until they're inevitable." And as she so passionately points out, it's time.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2020, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران