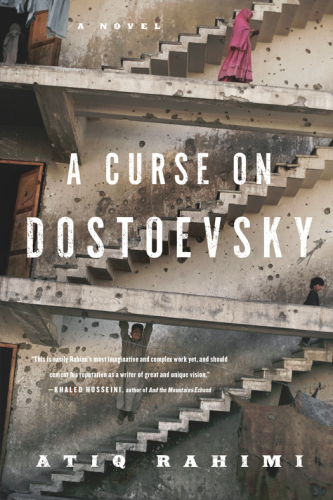

A Curse on Dostoevsky

A Novel

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

December 9, 2013

“The moment Rassoul lifts the axe to bring it down on the old woman’s head, the thought of Crime and Punishment flashes into his mind.” And so begins and ends Rahimi’s (The Patience Stone) hallucinatory tale. Rassoul, an aimless young Afghan man in Kabul, who, inspired by Dostoyevski, murders Nana Alia, a wealthy old woman who prostitutes Sophie, the woman he loves (Sonia to his Raskolnikov). While Rassoul thinks Crime and Punishment “is best read in Afghanistan,” the country’s chaos turns this retelling of a classic into a darkly comic meditation on life in a lawless land. Like Raskolnikov, Rassoul suffers moral pangs and stumbles around Kabul mute and existentially broken, puffing on cigarettes and hashish as he finds them. When he turns himself in to absolve his guilt, he faces the Kafkaesque absurd: “In our dear legal system, killing a madam is not murder... So... so something else must be causing you this distress.” Rassoul’s quest for punishment is rebuffed, and we are free to ponder the purgatory of unpunished sin. In restrained prose, Rahimi explores both the personal and the political; it’s both in dialogue with a classic and is daringly outspoken.

February 1, 2014

In war-torn Kabul, an admirer of Dostoevsky imitates Raskolnikov's murder of Alyona Ivanovna in Crime and Punishment--and suffers similar moral torment and self-loathing. At the beginning of Rahimi's narrative, Rassoul, the "new" Raskolnikov, kills Nana Alia. But before he can steal her money, he is scared off by the sound of a voice. As he runs away, he injures his ankle and curses Dostoevsky for having his "perfect crime" hindered by this unforeseen event. Like Raskolnikov, Rassoul is highly intelligent, self-reflective and morally conflicted. He also has a woman he's in love with--Sophia--who might in fact have been the voice he heard the night he murdered Nana Alia. (In Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov is morally "rescued" by Sonia, whose real name is Sofia.) Rassoul makes the difficult decision to return to the scene of the crime, something he knows he should not do. Also, as a result of his traumatic experience, he loses his voice and is forced to communicate by writing down notes. And while Rahimi frames Rassoul's experiences through a third-person recounting, Rassoul also keeps a journal of his activities and thoughts, and Rahimi offers generous glimpses into Rassoul's mind with this first-person account. The parallels to Dostoevsky's novel are striking, as, like Raskolnikov, Rassoul has issues with his landlord; he first confesses his crime to Sophia; and he has a relatively clueless mother. One irony is that, in Kabul, violence is so pervasive that people are being killed almost indiscriminately, so one more "murder" shouldn't make a difference, right? But it does. Rahimi does a masterful job both in echoing Dostoevsky and in updating the moral complexities his protagonist both creates and faces.

COPYRIGHT(2014) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

December 1, 2014

Afghan-born, Paris-based Rahimi, who's won the Prix Goncourt for his fiction and numerous awards for his films, daringly references Crime and Punishment from the first page of this page-turning novel. Rassoul takes an axe to the wealthy dowager who has prostituted his beloved Sophia and, true to Dostoyevsky, wishes to expiate his sin by surrendering to the police. But he's in war-torn Kabul, where absurdity reigns, and his efforts become ever more frantic and darkly hilarious.

Copyright 2014 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

Starred review from February 1, 2014

A subtle English translation delivers a French novel written by an Afghan novelist inspired by a Russian masterpiece. In a rare imaginative feat, Rahimi re-creates the superman-murderer Raskolnikov in the passionate Rassoul, a tortured soul living out his own tale of crime and punishment on the streets of Kabul. As he lifts an axe against the madam who has prostituted his beloved Sophia, this introspective protagonist recognizes that he has plunged into the same turbid depths he previously contemplated as a student of Dostoevsky. Rahim indeed deftly plays off Dostoevsky's themes as he probes not only the killer's individual conscience but also the collective moral and spiritual dilemmas of his native land. These dilemmas reflect the tragic consequences of protracted war pitting Soviet invaders galvanized by Communist ideology against native mujahideen steeped in ancient tradition and fired by Islamic zeal. In his quest for expiation and forgiveness, Rassoul finds hope in Sophia, just as Raskolnikov does in Sonja. In his hero's searing self-examination, Rahimi renews many of Dostoevsky's original psychological insights and opens piercing new ones. Unforgettable.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2014, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران