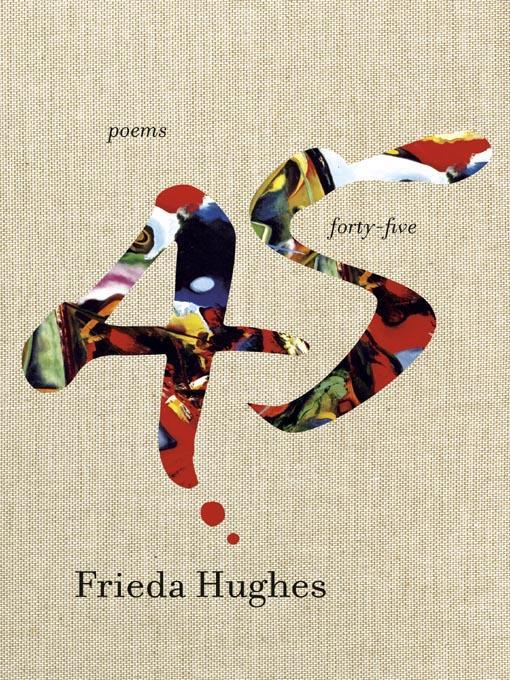

Forty-Five

Poems

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

September 18, 2006

The third effort from Hughes (Waxworks

, 2003) is by far the least polished, and the most confessional: the daughter of poets Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath offers one poem for each of the years of her life. Readers of Plath and the elder Hughes may recognize Frieda's parents in the manner of the poems as in the matter. Ted Hughes's autobiographical Birthday Letters

may provide fruitful comparisons, though Frieda Hughes looks more often at her own emotions than at others': "My mother, head in oven, died/ And me, already dead inside." Even as a child, Frieda reports, "I longed/ To fill the void in family/ Between father, aunt and brother-love." Subsequent poems follow her through "undiagnosed dyslexia" at school, borderline anorexia in her teens ("my fat removal/ A vain attempt to gain approval"), a glamorous but unsatisfying first husband, the dull frustration of jobs in sales and real estate, and the trials of chronic fatigue syndrome. Salvation comes through art school and, finally, through writing itself: "My poetry was where I hid/ When my father died." Readers in search of further information about Frieda Hughes's talented parents will find strong sentiments but no surprises; even those who admired this poet's earlier volumes may be taken aback by the artlessness on display.

November 1, 2006

The daughter of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes has published three previous poetry collections (e.g., "Waxworks"), but this collectionoffering one poem to convey the most dominant moment from each year of her life, written to accompany 45 paintings that she calls "an abstract landscape of my life"would seem to be her most autobiographical. The writing, unfortunately, is plagued with clichés. The six-year-old longs for "happier tomorrows." Her father, looking at her first poetry collection, "was beside himself with joy." At 41, rejected once again by her Cinderella-like stepmother, she addresses her dead father: "Daddy, Daddy, come and see/What she's done to me." (Dare one compare this to the power of Plath's "Daddy")? While these single-stanza poems don't go out of their way to rhyme, they don't shun it either, and the result is more clumsy than lyrical. Overall, they offer up a whining innocence that reeks of pretense; as painful as these memories must have been, the rough-edged emotions have been long ago worn smooth. The writing itself has little to recommend it, but far too many readers are also voyeurs, and library patrons will most likely queue up for it.Rochelle Ratner, formerly with "Soho Weekly News", New York

Copyright 2006 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران