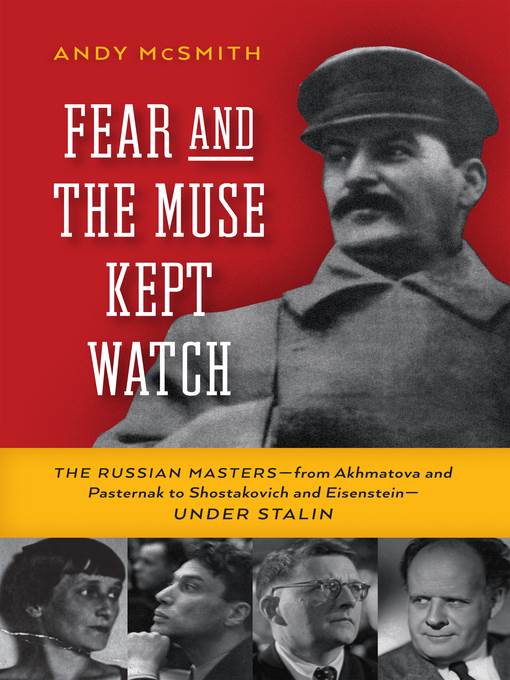

Fear and the Muse Kept Watch

The Russian Mastersfrom Akhmatova and Pasternak to Shostakovich and EisensteinUnder Stalin

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

May 18, 2015

In this study of artists living in the U.S.S.R. during Stalin’s reign, journalist McSmith (No Such Thing as Society) probes the question of why a “disproportionate amount of the great art of the 20th century came from a regime where to think freely was to risk death.” In addition to the creators mentioned in the title, the book delves deep into the lives of numerous poets, novelists, composers, and playwrights, including the likes of Isaac Babel, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Osip Mandelstam. The suffering is awfully apparent as McSmith describes each artist’s struggles—for the right to create, for artistic integrity, and for survival—“in a state where anybody could be punished for anything.” The persistence of both artists and appreciators of the arts is humbling. For example, Nadezhda Mandelstam, a widow in her 70s, preserved Mandelstam’s life’s work by memorizing all of it. The book stays strictly focused on the Soviet state, never segueing into a larger discussion of the social and political role of art under repressive regimes. Nevertheless, McSmith pieces together many stories in a way that is thoroughly engaging from start to finish.

May 1, 2015

Independent senior reporter McSmith (No Such Thing as Society: A History of Britain in the 1980s, 2010, etc.) explores how arts and artists in Russia somehow managed to flourish despite Joseph Stalin's iron control. Stalin decided whose work was acceptable. If it was not, it ended up in the ash heap-unless someone, like Pasternak or Gorky, interceded. The only literary style suitable in those days was social realism that lauded the Russian way of life. There were attempts to modernize, such as Sergei Eisenstein's addition of jazz to his films, and there were successes-e.g., his Battleship Potemkin (1925). Stalin knew that artistic success reflected on his regime, and he obsessively controlled everything, especially movies but also the music of Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Writers of poetry and plays all lived under his vigilance, as well. The greatest poets of the generation, under the eye of the censors, were never sure what would offend. Throughout his oppressive reign, Stalin had no problem sending artists to their deaths. Though he claimed that writers were the engineers of the human soul, every word written, every play or movie proposed was subject to review before, during, and after completion. McSmith shows how many persisted in the worst conditions and even returned after emigrating, for love of the homeland. Perhaps their strength came from knowing how much Russians loved the arts. Osip Mandelstam said, "there's no place where more people are killed for it." An epigram he wrote about Stalin was never written down, only recited twice, but the secret services still found out about it. Paranoia was a way of life. The author has a deep affinity for these artists, and his portrayal of their struggles makes our appreciation of them even stronger. Lovers of Russian literature and music will find this valuable, and history buffs will get a fearsome picture of life under Stalin.

COPYRIGHT(2015) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

July 1, 2015

McSmith writes journalist's history in the best sense, accounting for persons and events without resorting to theory, psychological or political. With clear-eyed restraint and unsentimental sympathy for the victims, he tells the story of Stalin's quarter-century effort, ended only by his death, to manage the greatest Russian artists of the time through intimidation, harassment, jailing, torture, and, when circumstances allowed, murder. He concentrates on the unquestionably greatest figuresfilmmaker Sergei Eisenstein; poets Vladimir Mayakovsky, Boris Pasternak, Anna Akhmatova, and Osip Mandelstam; composers Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev; playwright and novelist Mikhail Bulgakov; and short story master Isaac Babel. Some were ruined early: Mayakovsky committed suicide in 1930; Bulgakov decided to write The Master and Margarita for posterity. Eisenstein had to wholly change his style, the composers to water theirs down to mediocrity (Shostakovich lived to reassert himself; Prokofiev died the same day the dictator did). Mandelstam and Babel were shot. Pasternak and Akhmatova survived, in quite different circumstances, though both because the international renown gained in their youth stayed Stalin's hand. An invaluable contribution to serious popular history.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2015, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران