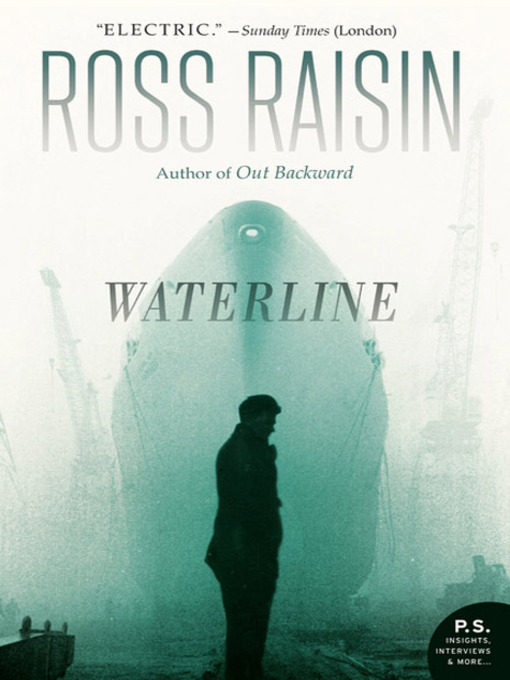

Waterline

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

December 12, 2011

Raisin’s (Out Backward) second novel is a powerful depiction of the dislocating effects of grief. Glasgow shipyard worker Mick Little is unmoored when his beloved wife, Cathy, dies of cancer. Blamed by his son for her death, Mick withdraws and slides into despondency and drink. Unable to bear the pitying stares of his friends or the memories of home, he moves to London, but finds few opportunities and little to distract him from his sorrows and submits to a dissolution scarcely imaginable. Raisin’s novel, written in a sometimes inscrutable brogue, does not unfold easily. The Beckettian repetition of mourning, numbness, and self-destruction mimics Mick’s disorientation and growing dysfunction. But the persistent reader will find his tragic fall and ultimate salvation genuinely moving. Mick is finely rendered as a man alienated by his love and guilt; his downward spiral feels painfully real. Raisin is as likely to linger on a moment of idleness as on Mick’s inchoate fury, capturing the cadences of depression and rage. The novel argues for patience and empathy in the face of self-inflicted ruin, even as Mick and his family struggle to find it for themselves. Agent: Rogers, Coleridge & White.

December 15, 2011

A working-class Glaswegian widower starts to drown under the weight of his own sorrow. In his second novel, Raisin (Out Backward, 2008) explores work, family and grief. While this book is a less showy, more introspective bit of fiction, it showcases the author's immense talent for occupying characters both through their inner lives and the ways in which they are perceived by those around them. A steadfastly Scottish novel, it opens on a funeral. Former shipbuilder Mick Little is suffering through the worst hard time. After years dragging his family around Australia before returning to Glasgow, he's lost his job as a minicab driver and his wife has just died. Worse, she died from the results of asbestos that Mick carried home on his clothes for decades. His son Robbie, in from Australia, tries to support his Da, but Mick's estranged son Craig can't hide his anger for his father's culpability. The in-laws, in from the Highlands, have taken over all arrangements, leaving Mick with no role in the tragedy of his life. "So this is grief, well," Raisin writes from inside his broken vessel. "Sat at the kitchen table with all your joys and your miseries sleeping and snoring about you and you sat there wondering what to do for your breakfast." This distinctly northern vernacular may be off-putting for readers, but, like with Irvine Welsh or James Kelman, the journey is worth the navigation. When he can't stand it anymore, Mick boards a bus bound for London, taking the meager savings earned from selling off the gold and trinkets left in his home. It's painful to watch as Raisin's beleaguered everyman slouches inevitably towards homelessness. But the author carries off his poignant meditation on the plight of the modern working man with an incisive absence of melodrama and an austere dignity. A compassionate portrait of a man on the verge filled with disquieting tension.

(COPYRIGHT (2011) KIRKUS REVIEWS/NIELSEN BUSINESS MEDIA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.)

دیدگاه کاربران