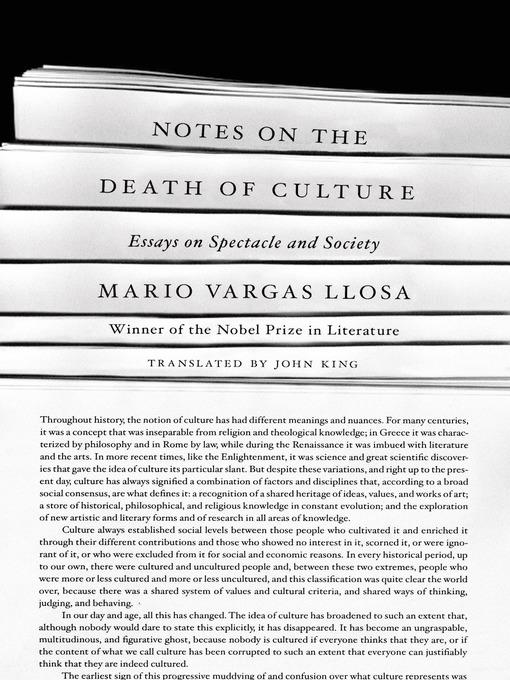

Notes on the Death of Culture

Essays on Spectacle and Society

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from March 9, 2015

One of the world's great literary figures, Peruvian Nobel Prize winner Vargas Llosa, now 78, offers a trenchant collection of long essays plus related articles written for El Pais, the Madrid newspaper. They approach required reading for any serious observer of arts and letters. To Vargas Llosa, the contemporary beau ideal is not substance or depth; the trendy and ambitious move increasingly toward inane, vulgar intellectual fashions like iron filings to magnets. "Frivolity disarms a sceptical culture," he warns. The book's first third comprises a long essay entitled "The Civilization of Spectacle," which was the original, less pessimistic title when this collection was first published in Spanish. More interested in self-promotion and exhibitionism than in substance, intellectuals "play the fashion game and become clowns." What passes for daring are in fact "masks of conformity." The author objects to a culture increasingly "pulling his leg," to a cultural establishment "complicit" in these caprices, and to a public being "manipulated and conned." Vargas Llosa fears a world hurtling toward special effects and Marshall McLuhan's "image bath." The disappearance of traditional books compounds the thrall of spectacle. Words, he reminds us in his conclusion, have the power to "delve into problems" and "tell the truth" in ways that "more enjoyable and entertaining" images cannot. An acid critique of Michel Foucault's and Jacques Derrida's confections, wherein it is "forbidden to forbid," broadens to the subsequent, abject collapse of educational authority. In "The Death of Eroticism," Vargas Llosa expresses wry amazement at the introduction of classroom masturbation workshops in sex education and the educators who think of this kind of thing as progress. In "Cold Sex," he connects such farce to the thought system of Catherine Millet, a French feminist and author of The Sexual Life of Catherine M., remarking on the "dehumanizing" results of liberated sexuality. "I end on a somewhat melancholic note," Vargas Llosa writes, for he believes the 21st-century world defines progress mainly as the satisfaction of material and power needs. Vargas Llosa has no illusions about spectacle's mass appeal and popularity, and he at once echoes and builds on earlier complaints of titans Daniel Bell (The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism), Christopher Lasch (The Culture of Narcissism), and Neil Postman (Amusing Ourselves to Death). In this diamond-hard, prophetic complaint, Vargas Llosa reiterates many known worries and cultural omens. His alchemy results in an imposing summa that's rich in common sense and perspective.

April 15, 2015

From the renowned Peruvian novelist and essayist, a survey of where Western culture finds itself these days-which is mostly nowhere. If the T.S. Eliot-inflected cultural criticism of the 1950s could be said to have a modern exponent, Vargas Llosa (The Discreet Hero, 2015, etc.), who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, might best wear the crown. (George Steiner is close, but he likes physics too much.) Vargas Llosa is conservative, arch, and classical; he agrees with his predecessor that the world of nuclear weapons and iPhones is "a blatant manifestation of barbarism" and that culture writ large is what makes life worth living. The essays in this collection take a predictably dim view of Marxism and of one unintended consequence of democratization, namely the democratization and dumbing-down of culture-with the "undesired effect of trivializing and cheapening cultural life." There's a certain get-off-my-lawn quality to some of Vargas Llosa's complaints, but just when he seems to be falling into tired golden-age reveries, he turns on the heat. If people were better educated, he suggests, they'd be more worthy of democracy, but for the time being, they can't be bothered to be bothered by the pandemic corruption that governs the world. If people were more cultured, we might have better cultures in which to live. If capitalism were less venal, then perhaps the cultural world would be less the province of "thinkers and artists with mediocre or zero talent but who are very bright and flamboyant, who are skilled self-publicists or who know how to pander to the worst instincts of the public." Of a piece with late writings by Hilton Kramer, Hugh Kenner, and even Steiner; sometimes pat but offering fresh interpretations and sharp criticisms of things as they are.

COPYRIGHT(2015) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

January 1, 2015

Who better than a Nobel Prize winner in literature to discuss the concept of culture? Vargas Llosa here references T.S. Eliot's "Notes Toward a Definition of Culture," which envisions a vital complex of ideas, beliefs, and values resting on the past and moving us forward. Now culture means mostly entertainment, he argues; we lack an intellectual life driven by public figures. Jump-starting the conversation.

Copyright 2015 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران