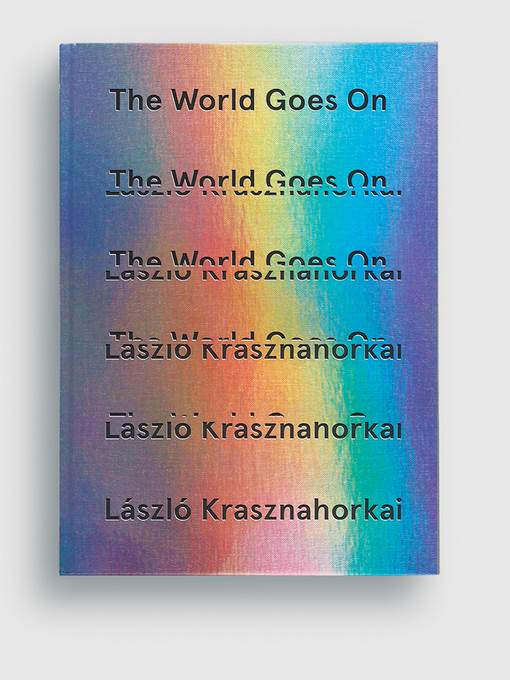

The World Goes On

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from September 4, 2017

Krasznahorkai’s latest begins in a void, out of which speaks a voice who wants to escape the world, where everything “is intolerable, unbearable, cold, sad, bleak, and deathly.” From there, the speaker embarks on a series of monologues in which he circles the globe, tries to outrun it, wants to forget it, then delivers three lectures on melancholy, revolt, and possession. These exercises concluded, a set of enigmatic short stories unfold. In “Nine Dragon Crossing,” a man obsessed with waterfalls becomes lost in contemplation of the winding streets of Shanghai. In “One Time on the 381,” a Portuguese miner stumbles upon a buried palace. The iconoclastic filmmaker of “György Fehér’s Henrik Mólnar” recalls Krasznahorkai’s own collaborations with director Bela Tarr. The ecstatic “A Drop of Water” concerns an encounter with a Buddha on the banks of the Ganges. Other stories take readers to a baroque and sensual Venice or resume the theme of leaving the world through the story of Russian cosmonaut Gagarin. In the end, the storyteller bids farewell and departs into eternity, leaving readers to puzzle over the parables, dialogues, and tales. This book breaks all conventions and tests the very limits of language, resulting in a transcendent, astounding experience.

August 15, 2017

The world goes on indeed, and it's not pretty: so Hungarian novelist Krasznahorkai (The Last Wolf and Herman, 2016, etc.) instructs in this existentialism-tinged set of linked stories.It could just be the Rivotril talking, but when Krasznahorkai's narrator gets going on the subject of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, it quickly turns into a conspiracy theory full of ominous warnings about shadowy doctors, vodka, and the KGB: "Gagarin had to disappear for good, and of course, the way in which he died--that one of the nations, indeed one of the world's greatest heroes would perish due to such a simple test flight--was inconceivable, I had to understand this...." The Gagarin story opens on an urgent note of leave-taking: "I don't want to die," Krasznahorkai writes, "just to leave the Earth," which subtly echoes the opening words of the collection itself: "I have to leave this place, because this is not the place where anyone can be, and where it would be worthwhile to remain...." That echo sounds at many points throughout the book, a whirlwind of sentences that run on for 10 pages and more at a time and that evoke a world-weary pessimism over human beings and their strange ways. Renouncing the very promise of salvation, a bishop declares that "no one shall attain heavenly Jerusalem," adding, "and the distance which leads to Your Son is unutterable," while on a more terrestrial plane, a banker grumbles over audits and paper trails and fearful CEOs. The spirit of James Joyce hovers over Krasznahorkai's pages, and Nietzsche is never far away, either; indeed, the German philosopher appears early on, breaking down into madness on witnessing a horse being whipped in a Turinese street. In dense, philosophically charged prose, Krasznahorkai questions language, history, and what we take to be facts, all the while rocketing from one corner of the world to the next, from Budapest to Varanasi and Okinawa, all places eminently worthy of being left behind. Complex and difficult, as are all of Krasznahorkai's works, but worth sticking with.

COPYRIGHT(2017) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

December 1, 2017

In the opening piece in Man Booker International Prize winner Krasznahorkai's near-mystical new work, a wanderer seeking to leave a forbidding place at first finds his hands and feet bound, then manages a "forced march" before falling over exhausted and realizing that he will die "there at home, where everything is cold and sad." Rather like life darkly perceived or the depths of depression. The piece perfectly sets up what follows: dense, stylized meditations that aren't exactly fiction or essay or philosophical treatise but something sui generis, representative of Krasznahorkai's unique mind. A lecturer's investigation of melancholy, reflections on moral law inspired by Nietzsche's paralysis after witnessing a horse's beating--these are the wonders and challenges found here. VERDICT Definitely for high-end readers; for the curious, a good place to start.

Copyright 2017 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران