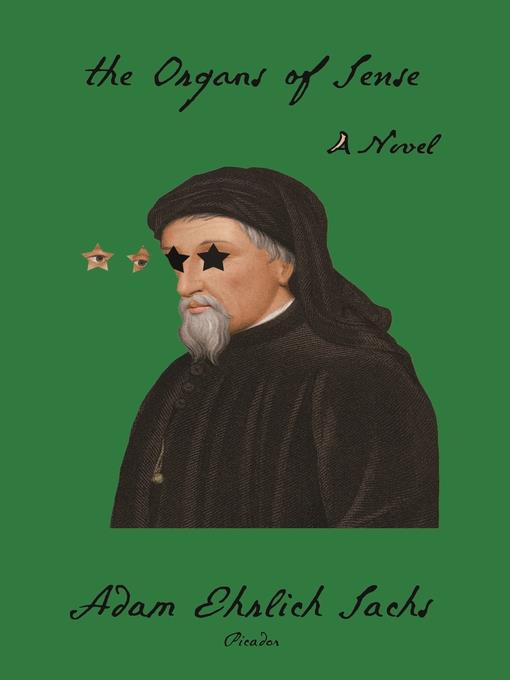

The Organs of Sense

A Novel

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from March 4, 2019

In his sublime first novel (following the story collection Inherited Disorders), which recalls the nested monologues of Thomas Bernhard and the cerebral farces of Donald Antrim, Sachs demonstrates the difficulty of getting inside other people’s heads (literally and figuratively) and out of one’s own. In 1666, a young Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz—the philosopher who invented calculus—treks to the Bohemian mountains to “rigorously but surreptitiously assess” the sanity of an eyeless, unnamed astronomer who is predicting an impending eclipse. Should the blind recluse’s prediction come to pass, Leibniz reasons, it would leave “the laws of optics in a shambles... and the human eye in a state of disgrace.” In the hours leading up to the expected eclipse, the astronomer, whose father was Emperor Maximilian’s Imperial Sculptor (and the fabricator of an ingenious mechanical head), tells Leibniz his story. As a young man still in possession of his sight, he became Emperor Rudolf’s Imperial Astronomer in Prague, commissioning ever longer telescopes, an “astral tube” whose exorbitant cost “seemed to spell the end of the Holy Roman Empire.” The astronomer also recounts his entanglements with the Hapsburgs, “a dead and damned family,” all of whom were mad or feigning madness. These transfixing, mordantly funny encounters with violent sons and hypochondriacal daughters stage the same dramas of revelation and concealment, reason and lunacy, doubt and faith, and influence and skepticism playing out between the astronomer and Leibniz. How it all comes together gives the book the feel of an intellectual thriller. Sachs’s talent is on full display in this brilliant work of visionary absurdism.

March 15, 2019

Mix Umberto Eco and Thomas Pynchon, add dashes of Liu Cixin and Isaac Asimov, and you'll approach this lively novel of early science.Being an astronomer in the days before high-powered telescopes were developed was not an easy job, especially for the sightless but productive astronomer at the center of Sachs' (Inherited Disorders, 2016) literate, quietly humorous historical novel. The astronomer in question, who, notes protagonist Gottfried Leibniz--yes, that Leibniz, polymathic philosopher and inventor of calculus--is "in fact entirely without eyes," has predicted, to the very moment, that at noon on the last day of June 1666 a profound solar eclipse will plunge all Europe into temporary darkness. Given that no other astronomer has arrived at this forecast, Leibniz is intrigued, and off he goes to find the astronomer and gauge whether he is truly blind and truly not off his rocker: "So, if he is sane, and he has not detected me, then this is not a performance, and either he really sees, or he thinks he really sees." Given that the year 1666 has been an ugly one of plague and war and anti-scientific purges, there's plenty of reason not to want to see. The astronomer has much to say about such things, spinning intricate tales, some of them increasingly improbable. There's a gentle goofiness at work in Sachs' pages, as when he constructs a syllogism about the relative movements of thinkers and nonthinkers, concluding that "if you look very closely at a nonthinker and a true thinker you'll notice that they're actually standing still in completely different ways," and when a prince reasons that in order to call a dog a dog, the thing has to love us, whereas "before that point we call it a wolf." Yet there's an elegant meditation at play, too, on how science is done, how political power can subvert it (in the astronomer's case, in the form of onerous taxes), and how we know the world around us, all impeccably written.A pleasure to read, especially for the scientifically inclined.

COPYRIGHT(2019) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Starred review from May 1, 2019

Deep in the mountains of Bohemia in 1666, a blind astronomer has made a bold prediction. He has forecast the exact time for the next solar eclipse. The wrinkle is, the astronomer is not just blind; he has no eyes. His case attracts the attention of polymath Gottfried Leibniz, who treks to Schwarzenberg to find out what gives. This is how Sachs kicks off his beguiling and utterly magical first novel, in which the unnamed astronomer narrates his personal history with the clock ticking down to the much-awaited celestial event. What unfolds is a riveting story about geopolitical scheming, warfare, and the reach of the Catholic League in the seventeenth century. At the novel's beating heart, though, is a much more universal theme as Sachs considers father-son relationships and other complicated family dynamics that can make or break creative ambitions of all stripes; add to that how the astronomer's singular focus on cataloguing all the known stars of the universe is constrained within a personal and more frayed canvas. Sprinkled with generous doses of philosophy, this gem of a novel, with a spectacular denouement, might make for labored reading initially, but ultimately, it's an utterly immersive and transportive work of art.(Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2019, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران