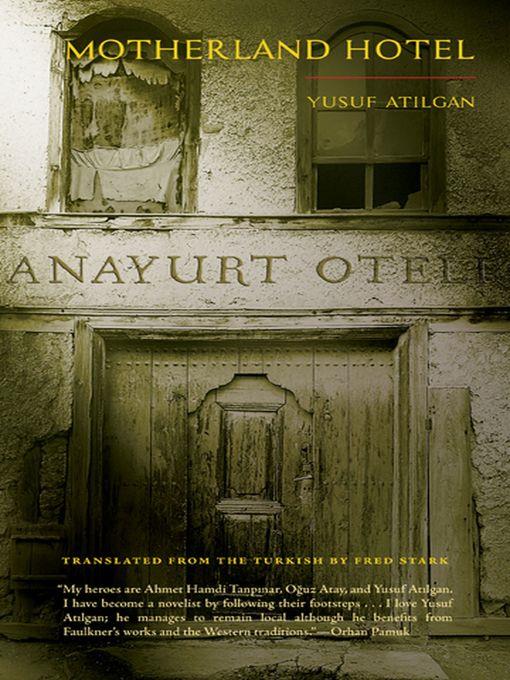

Motherland Hotel

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

August 15, 2016

Descent into madness is swift in Turkish literary pioneer Atilgan’s novel, first published in his home country in 1973. Dutiful hotelier Zeberjet lapses often into harried, solipsistic fits after spending most of his life as a “serious and patient” (if not particularly upstanding) bore in Izmir. Attending carefully to the bookkeeping and clerkship at the titular hotel—a converted estate passed to him by his grandfather—he forces himself on the hotel’s resigned maid, skims a pittance from the business’s proceeds, and passes room keys to travelers and johns alike, withholding judgment based less on a live-and-let-live philosophy than an apparent lack of interest. When a mysterious female guest leaves a bath towel behind, Zeberjet becomes increasingly engrossed in the possibility of seeing her again. As the obsession grows, he starts to break from his routines, ditching work to play flaneur, eavesdropping on strangers in town, attending a cockfight, and briefly entertaining the courtship of a young man. As a history of familial bad luck and sexual trauma is unraveled, Zeberjet’s slide—from minor, private invention to antisocial eruption—begins to seem fated. Automatic writing diehards will cherish the Woolfian outbursts Atilgan churns into the straightforward prose, though in Stark’s translation—completed back in 1977—the digressions occasionally succumb to an incoherence.

Turkish writer Atilgan's classic 1973 novel about alienation, obsession, and precipitous decline, nimbly translated by Stark.Zeberjet is the owner of the Motherland Hotel, formerly his ancestral home in Izmir, Turkey. Defined less by his nebulous personality than the invariable order of his days, he rises at 6 a.m., takes tea with one lump at 7, visits the barber every four weeks, the public bath every six months, and violates the hotel's charwoman on a near-nightly basis--until the night an alluring woman from Ankara stops in on the way to her village. Though her stay is brief and the conversation minimal, Zeberjet's obsession takes hold while he keeps her room just as she left it and visits nightly, the details of their interaction repeatedly intruding on his thoughts. When he accidentally drops and shatters her teacup, he believes all chance of her returning destroyed along with it, leaving him free to plummet into complete debasement. Later, enraged at his own impotence, Zeberjet murders the charwoman, along with her cat, whereafter he dreams of being put on trial, not for the murder of his employee, but her pet, as his attorney winks, putting a tidy point on the treatment of women all around him. As his life narrows to exclude all but compulsion and dissimulation, he wafts through town as we slip in and out of his turbulent stream-of-consciousness, snippets of conversation drifting in and sticking to his jumbled thoughts, mixing with memory, fantasy, and family history. Everywhere he goes, Zeberjet encounters another crime, in fact or in retelling, recent or ancient, woven into the very fabric that makes up his world, and is "embarrassed, ashamed actually, before all those people who thought of themselves as innocent, who failed to realize that only crime--some kind of crime--could keep you alive on this earth." An unsettling study of a mind, steeped in violence, dropping off the edge of reason. COPYRIGHT(1) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

October 1, 2016

A maladroit loner who runs the seen-better-days Motherland Hotel in a backwater Turkish town, Zeberjet has become obsessed with a female guest who stayed there briefly and frantically anticipates her presumed return. The terse, stream-of-description narrative follows him as he tends to his guests, sleeps dispassionately with the hotel's hapless maid, and reflects on his long-gone family's history and relationship to the hotel, a grand mansion burned down by the Greek army in 1922. These details at first seem mundane, even tedious, but as Zeberjet becomes increasingly unhinged, we're drawn into his dark interior life while coming to understand Turkey's post-Ottoman uncertainty. (The novel was originally published in 1973.) Then a horrific and unexpected act of violence compels the narrative forward. VERDICT Sophisticated readers will understand why Atilgan is called the father of Turkish modernism, while those who enjoy dark psychological novels can also appreciate.

Copyright 2016 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران