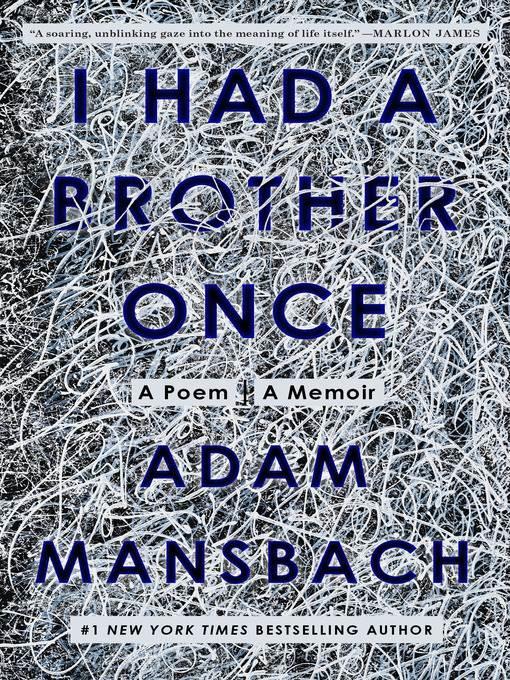

I Had a Brother Once

A Poem, A Memoir

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

March 1, 2021

Mere weeks before the release of Mansbach's runaway best-seller, Go the F**k to Sleep (2011), his younger brother took his own life. The author toured and promoted that hilarious parody of a children's book, all the while privately grieving this unthinkable loss. In this heartbreaking, brutally candid memoir, Mansbach employs long stanzas of free verse to recount events surrounding his brother's death, struggling through anger, sorrow, and confusion. Poetic conventions allow him to retreat into form, to distill the endless refrains of condolence in a way that recreates the time grief occupies in tragedy's immediate aftermath. As the speaker confides early on, before confronting the inevitable, "i would live / here in this preamble / forever." What follows is a series of emotional gut-punches, whether it be the brothers' Jewish ancestors ("the famous / rabbis' kids, the minyan-makers / of burlington vermont") looking down in disbelief or the father of the deceased sitting shiva while a Roman Catholic priest talks about his son. Throughout, Mansbach adds detached commentary that, while not exactly humorous, leavens the severity of the sudden loss. For an author who has written everything from screenplays to middle-grade novels to wildly popular picture books, this courageous and devastating memoir in verse stands out.

COPYRIGHT(2021) Booklist, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

April 1, 2021

A piercing poetic meditation on death, grief, and family. Among acclaimed novels and other works, Mansbach may be best known for his zeitgeist-grabbing children's book Go the Fuck To Sleep (2011). Here, he turns to weightier matters in this free-verse account of the suicide of his brother, David. "i could tell you / a few stories about stories, / flip a little wordplay, we could / warm up with some improv / games. it has been eight / fucking years & i have written / everything but this," he writes, immediately before telling of how he learned the news. His father called to say, "david has taken his own life," to which his response was a dull "what?" Of all the many regrets that ensued, Mansbach writes, a small but obviously unresolved one is that he made his father "say it to me twice." Small revelations abound: David suffered from depression, was incommunicative as a child, was perhaps on the autism spectrum: "his intelligence clustered in / an unfamiliar quadrant, / was not fierce & literary / but curious, methodical, & / this was foreign, hard / to see at first." While his first reaction, he notes, was to utter "banshee sounds," he sought explanation in family history and discussions with others whose siblings committed suicide--not a support group or "a meeting of suicide / survivors, that is the / tortured, oxymoronic / nomenclature for the / people left behind," but rather shattered individuals such as a bookseller who worked through his grief via memoirs by schizophrenics who wrote in times before there was even a word for their condition. In the end, writing that "the only thing worse than not understanding would be to understand," Mansbach turns to his daughters with the plea that they outlive him and a promise to his brother: "i will not let you go." A wounded though loving paean that will speak to anyone who has lost a sibling, no matter the cause of death.

COPYRIGHT(2021) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

دیدگاه کاربران