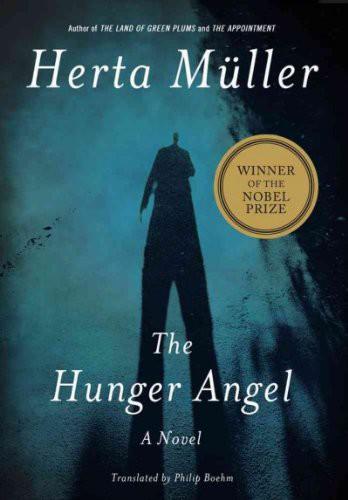

The Hunger Angel

A Novel

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

Starred review from April 30, 2012

Müller (The Land of Green Plums), winner of the 2009 Nobel Prize for Literature, introduces readers to Leo Auberg, a young closeted homosexual German-Romanian who recalls in powerfully vivid vignettes the delirium of the five "skinandbones" years he spent in a Soviet forced labor camp. Charged with "rebuilding" the war-torn Soviet Union, workers struggle under the specter of the figurative "hunger angel" and the work camp's absurd mathematics of misery, which hold that "1 shovel load = 1 gram bread." Leo's voice is wry and poetic, and Müller's evocative language makes the abstract concrete as her narrator's sanity is stretched; Leo posits that "Hunger is an object," and that death lives in the hollows of the cheeks as a white hare. Indeed, Leo's grimly surreal meditations on hunger seem all the more true for their strangeness; the cold slag in which he toils smells "a little like lilacs" and his "sweaty neck like honey tea." Juxtaposed with Leo's musings are observations on life in the camp, and brief dramas with other workers. Under Müller's influence, the subject matter not only begs a reader's sympathy, but deftly illuminates the complex psychological state of starvation and displacement, wherein the physical world is reconstituted according to the skewed architecture of oppression and suffering. Boehm's translation preserves the integrity of Müller's gorgeous prose, and Leo's despondent reveries are at once tragic and engrossing.

April 15, 2012

This novel of the Gulag was first published in Germany in 2009, the same year that its German-Romanian author won the Nobel Prize. Muller was born in 1953 and raised in a German-speaking enclave of Romania. In 1945 the Red Army had deported thousands from these enclaves to forced labor camps on the Russian steppe. Years later, the recollections of one of the former deportees inspired her to write this novel. Her narrator, 17-year-old Leo Auberg, has just started having sex with men in the park, fearfully, risking jail; when the soldiers come calling, he's glad to escape his watchful small town. That gladness disappears on the cattle cars. Dignity goes too, as the deportees are ordered off the train to do their business in a snowy field. What follows are dozens of short sections as Leo riffs on conditions in the camp. He will do different kinds of work: unloading coal, servicing the boilers, loading pitch in a trench. That last assignment is life-threatening, but before he succumbs to a fever Leo notes that "the air shimmered, like an organza cape made of glass dust." The poetic sensibility sets the novel apart. There is a much-hated adjutant, a German like themselves, but it is hunger, death's henchman, that is their greatest adversary. Leo fights it in practical ways: begging door to door, saving or trading his bread (echoes of Solzhenitsyn). But he also uses a kind of reverse psychology when he calls this devil hunger an angel. The inversion is crucial to Leo's morale and survival. Keep the enemy off balance. Flatter him; be gallant. This may sound whimsical, but there is steel in the writing. Muller's work is not without flaws. Leo's sexual orientation is not well integrated into the narrative; his post-camp experiences are too compressed. The novel is still a notable addition to labor camp literature.

COPYRIGHT(2012) Kirkus Reviews, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

December 1, 2011

Winner of the Nobel Prize, as well as the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and European Literary Prize, Muller is a writer to know. Here, teenaged Leo Auberg is picked up by a patrol in January 1945 and promptly taken to a camp in the Soviet Union, where he spends the next five years slaving in a coke-processing plant. Profound hunger makes him see the world in almost hallucinatory detail, and Muller is said to deliver a sharp sense of life reduced to the minimum: the heart merely a mechanism, thumping like a shovel meeting coal, and sand, snow, and cold acting almost as malevolent forces on their own. Since Muller was hounded from her job in her native Romania for failure to cooperate with Ceausescu's secret police, eventually managing to immigrate to Berlin, she has an intimate understanding of totalitarianism's particular terror that should come through here.

Copyright 2011 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

دیدگاه کاربران