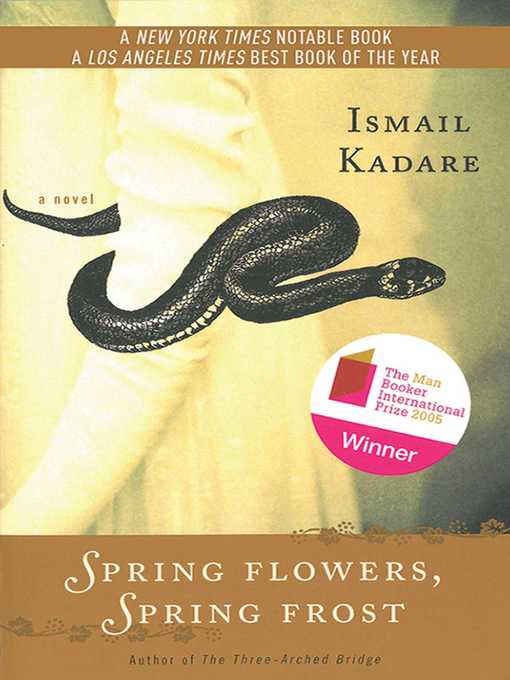

Spring Flowers, Spring Frost

A Novel

کتاب های مرتبط

- اطلاعات

- نقد و بررسی

- دیدگاه کاربران

نقد و بررسی

May 27, 2002

Working at the intersection of allegory and reality, Kadare (The Three-Arched Bridge, etc.) balances the forces of expression and repression in his latest novel, about an Albanian artist who struggles to keep his sense of equilibrium when the post-Communist government threatens to bring back the so-called "blood laws," which dictated behavior in the country's medieval past. Mark Gurabardhi is the protagonist, a sensitive soul who finds himself disturbed by political events in his strife-torn country, as well as by a bizarre bank robbery and a strange, lurid report that an attractive young woman has married a snake. Closer to home, Gurabardhi's relationship with his girlfriend—who also models for him—is an up-and-down affair, but what changes the artist's situation is the sudden death of his boss, the director of the art center, who is killed in murky circumstances. His death prompts Gurabardhi to investigate the rumor that the repressive government is about to reintroduce the ancient, family-oriented blood laws to help tighten their control of artistic expression. To learn more, Gurabardhi finds a way to eavesdrop on a conference of prominent leaders. The political turns personal when the artist's girlfriend reveals that her brother is being hunted by the state, and the book closes with the artist making a formal inquiry to the police chief to see if the old laws will be reinstated. Kadare's plotting is sometimes spotty and disjunctive, but despite the lack of continuity, each scene is as tight as the writer's razor-sharp prose. The juxtaposition of ideas and bizarre images is alternately beautiful, peculiar and provocative, as Kadare once again provides an excellent glimpse at the difficult nature of life in a politically unstable land.

Starred review from June 15, 2002

Novelist and poet Kadare (Elegy for Kosovo), long considered Albania's foremost author, here depicts the time following Albania's liberation from the Communist totalitarian government. Protagonist Mark finds himself caught between the jubilation of a tantalizing freedom and the social chaos that has accompanied it. Ancient beliefs and practices suppressed by the state resurface to create a new reign of terror. Mark becomes obsessed with Greek and Balkan legend, confusing these stories with both the tyranny and crimes of past leaders and the current disappearances and arrests of friends and fellow artists. Eventually, his dreams and nightmares merge with the nightmares and uncertainty of his daily life, and Mark finds that his long-awaited freedom has disintegrated into lunacy. In the latest of his many novels to be translated into English, Kadare artfully portrays how an individual is affected when his society is suddenly released from long oppression. Highly recommended for both public and academic libraries. Rebecca Stuhr, Grinnell Coll. Libs., IA

Copyright 2002 Library Journal, LLC Used with permission.

Starred review from June 1, 2002

\deflang1033\pard\plain\f3\fs24 Kadare's seventh translated novel is a rich, symbolic questioning of humanity's capacity for creating a murderless society. It proceeds in two complementary continuities. One is realistic and consists of chapters; the other, mythological, consists of "counter-chapters." The realist strand follows Mark Gurabardhi, an artist who works with a small city's cultural center, through several late-summer days during which his young lover visits him as he paints her nude portrait, and his boss at the center is assassinated, apparently in a revival, after Communist suppression, of Albania's age-old system of blood atonement between families. The mythological strand relates old legends, Mark's dreams, and the dirge of those drowned in the Strait of Otranto, fleeing Albania. Finally the strands converge, and Mark sees the ostensibly dead tyrants Brezhnev, Ulbricht, and Albania's own Hoxha gather near the disused tunnel where the record of all the blood-debts in Albania may have been hidden. Does a society repress vengeance only by industrializing murder? At last, eyeless Oedipus appears, "seeking the mysterious door to the tunnel from which he had once, by mistake, emerged" and coming to this tunnel that looks, to Mark, like his lover's sex. The predicament of human community, which may be human nature, is enough to send any man cowering back to the womb. Philosophical fiction of great poetry and power. (Reprinted with permission of Booklist, copyright 2002, American Library Association.)

دیدگاه کاربران